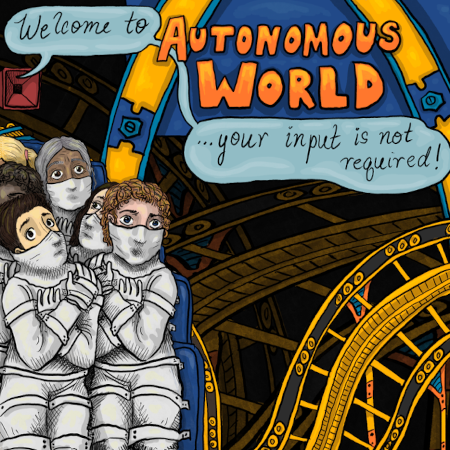

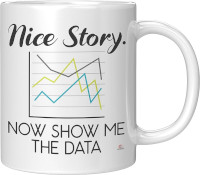

I once had a colleague that had a mug that looked like this:

You probably recognize this sentiment. W. E. Deming summarized it well with a quip: "In God we trust, all others must bring data." Data is cold, hard truth, while people are warm, wet, squishy, emotional, and unreliable. Rational and intelligent people base their decisions not on mere anecdote, but on numbers. God forbid we sink further beneath anecdote, which is at least still a fact, to ideology, morality, or, even worse, feelings. In our technologically-advanced society, there's no room for that kind of hysteria.

We no longer have propaganda and counter-propaganda, but information and disinformation. Propaganda implies a world with human agency, in which we are being actively courted by its authors, albeit sometimes by unscrupulous means. Information, on the other hand, is data, also known as truth, and those who disagree have disinformation, which is wrong data, an untruth. Today, accusing someone of writing propaganda is to accuse them of contaminating their information with ideology, which taints the pure data with its human irrationality.

This logic (or is it a feeling?) has so fully permeated our society that we often use it in reverse. When I incorporated my most recent venture, I sought advice on whether it should be for-profit or a nonprofit. More than once, I was told to choose for-profit, because then you have "a number" that you all agree is your objective measure of success. It's easier to run an organization if the social labor of coming together to decide its purpose can be outsourced to a heuristic, circumventing difficult conversations, and avoiding all that soft human stuff. Instead of using numbers to inform our decisions, we make decisions that will generate numbers.

We see this same perversion in our national, political conversations. Recently, Paul Krugman wrote a series of articles about inflation that proved controversial. His main argument was that, despite the many protestations, inflation isn't actually that bad. He called this "Disinflation Denial." He went back and forth with others about the specifics of how he measured inflation, which others pointed out removed housing, used cars, food, and energy (you know, the stuff poor people use). To his credit, he engaged with that critique, but the details of the discussion don't matter to us. More interesting is the sentiment that people are somehow wrong about our experience, and that these numbers prove it. The media is full of this kind of thing. Here's CNN: "Why Biden’s strong economy feels so bad to most Americans."

What’s the biggest problem with the US economy right now? The vibes are off.

By almost any objective measure, Americans are doing much better economically than they were nearly three years ago, when President Joe Biden took office. Still, a majority — 58% — say Biden’s policies have made economic conditions worse, according to a new CNN Poll conducted by SSRS.

That’s up from 50% a year ago.

But the grim outlook is at odds with the hard data, which reveal an economy bursting with optimism.

"Has the economy improved under Joe Biden? There’s literally no question," said Justin Wolfers, a professor of public policy and economics at the University of Michigan.

In January 2021, the start of Biden’s term, "everything sucked," according to Wolfers. Unemployment was at 6.3% and the economy had yet to rebound from the shock of Covid-19. Wolfers described that time as "one of the worst economic moments of my life."

Notice the derision with which they treat public opinion about the economy, mockingly comparing our plebeian "vibes"-based understanding with reality, as represented by "objective measure[s]." Like Krugman, they seem frustrated by our claims that our material reality dare defy the sacred metrics, which are transubstantiated truth itself. They've forgotten that the point of metrics is to describe reality, not dictate it. Economic metrics specifically exist to help us describe the economy, a completely abstract concept that we invented to help us understand our collective project of social reproduction. It is not an actual, material thing. It is a model, a useful abstraction, but that doesn't stop people in positions of power from arguing that we should let our sick and elderly die for its sake. This is two layers of backwards. Metrics are supposed to describe the economy, and the economy is supposed to describe how we provide for our material well-being. Instead, we're being asked to die, the opposite of well-being, to boost its numbers.

We're so used to being talked down to this way that we cower at the mere suggestion of data. Self-driving cars were presumed to be safer than human drivers before anyone had ever even seen one. Their advocates argued from the beginning that humans are fallible and prone to irrational judgment, whereas the cold and unfeeling autonomous machines, which didn't yet exist, are still somehow necessarily safer. They argued this not only before there was data to back up their claim, but before it was possible to generate such data, and we still took their arguments seriously, even though it should be obvious to anyone that you can't base an argument on future data. Here's the New York Times, all the way in 2010, covering one of the early prototypes of such a device:

Robot drivers react faster than humans, have 360-degree perception and do not get distracted, sleepy or intoxicated, the engineers argue. They speak in terms of lives saved and injuries avoided more than 37,000 people died in car accidents in the United States in 2008. The engineers say the technology could double the capacity of roads by allowing cars to drive more safely while closer together. Because the robot cars would eventually be less likely to crash, they could be built lighter, reducing fuel consumption. But of course, to be truly safer, the cars must be far more reliable than, say, today’s personal computers, which crash on occasion and are frequently infected.

Notice that absurd comparison. They compare actual, real human driving statistics with the robot cars that will "eventually be less likely to crash." That's fundamentally nonsense, but they're somehow so confident that they report that the cars won't even need physical safety features, which I can only assume translates to cost-savings for the manufacturers. We instinctively offer our submission as soon as there might be numbers, to the delight of tech companies with warehouses full of the stuff.

Except last year, there actually was some real data about self-driving cars, and Cory Doctorow noted just how abysmally they did when compared to humans. To date, I have yet to see any convincing data that self-driving cars are better than humans. I've seen some self-reporting from the very same company that just had its license revoked for dishonesty, on top of recent reporting that these companies employ 1.5 staff-members per car, intervening to assist these not-so-self driving vehicles every 2.5-5 miles, making them actually less autonomous than regular cars. Even then, they've caused constant problems, but we have so much faith in cold, rational machines, and so little in each other, that the narrative lives on.

I am not the first to observe this phenomenon. Here are Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer,1 writing all the way back in 1944, succinctly articulating it:

For enlightenment, anything which does not conform to the standard of calculability and utility must be viewed with suspicion.

But we've now entered a new phase. Before, we were suspicious of anything that couldn't be turned into numbers, but now, we have the computer, a machine capable of turning anything and everything into numbers. We no longer even need to harbor that suspicion of the incalculable. We can simply banish it, probably with a spreadsheet, or a metric, or even an annoying mug.

I don't mean this as an abstract rhetorical flourish. This is something totally normal that we do all the time without realizing it. When deciding how much to value websites or podcasts or any other online media, we simply add up the number of downloads. No one actually thinks that's a good way to decide the value of art, writing, journalism, story-telling, lascivious true crime blogs, or reality TV rewatch podcasts. It's just the first number that fell out of a computer. Just like that, a complex social situation was transmuted into a number. Adorno and Horkheimer also saw this coming, fully 90 years ago, in that same essay:

Bourgeois society is ruled by equivalence. It makes dissimilar things comparable by reducing them to abstract quantities. For the Enlightenment, anything which cannot be resolved into numbers, and ultimately into one, is illusion[.]

The absurdity of collapsing every piece of digital media into downloads, as if not absurd enough already on its face, has recently been made even more clear: Changes to the Apple podcast app's downloading functionality is going to reduce podcast revenue. Arbitrary changes to the Apple podcast app don't actually change the podcasts, but here, like in all things, we "follow the data," an oft-repeated oath of loyalty to the statistically-generated regime.

We value data so much more than human agency that we genuinely believed (or maybe still believe?) that, given all the polls and demographics, Nate Silver could divine the results of every American presidential election. This belief in technocratic determinism is antithetical to democracy. Democracy is something you do. It's the process by which we exercise our agency. But not only do we believe in technological divination, we act on it, thereby manifesting it. There is much discussion about whether Democrats should run candidates in so-called "red" states. Right now, they often let those races go uncontested. This decision makes sense from a data perspective: Why invest $X into an election in a district where Republicans have a +Y lead when that money could better influence 3 other elections, where Republicans only have a Y/3 lead? This is the process by which we get Joe Biden, a statistically generated median in corporeal form. He's literally a franchise reboot, the single most derivative but fiscally sound cultural product. But that question, seen from an ideological perspective, rather than a financial one, has a straightforward and obvious answer: Because that's how democracy works. The act of choosing matters. We wish to exercise agency over our lives, not have it predetermined by spreadsheets.

Instead, many aspects of our daily lives are dictated by arbitrary calculations, often tragically. Turn on the news, and in between the horrifying stories of war and climate catastrophe, you'll learn that the Dow is up 18 points. It seems silly until it goes down enough and we all lose our jobs. Like so many major social questions, we've decided to put the ownership of all our assets through computers to turn it into data, avoiding those historically touchy conversations about who should own the means of production. These numbers, when they go low enough, cause mass evictions, during which the police forcibly remove people from their homes, following orders from a chain of command that ultimately ends at the data itself.

Here's Adorno and Horkheimer again, speaking specifically about mass entertainment, but making an argument that generalizes well:

Films and radio no longer need to present themselves as art. The truth that they are nothing but business is used as an ideology to legitimize the trash they intentionally produce. They call themselves industries, and the published figures for their directors' incomes quell any doubts about the social necessity of their finished products.

Again prescient. It's now part of mainstream political ideology to run things "like a business," such that every institution, from school boards to nation states, is no longer literate to anything but finances and metrics. These institutions are incapable of redressing our immeasurable political grievances precisely because they're run like businesses. When they can't see our problems in their data, they, like Krugman and CNN, chastise us for our irrationality. The result is automated and self-fulfilling institutional cowardice, depriving us of political agency by reflexively demanding data, thereby circumventing the necessary social labor that progress demands. Unsurprisingly, faith in American institutions is at an all-time low.

These numbers that we generate, for all their many absurdities, have (at least) one more fundamental flaw. A number is meaningless without units. 4 gallons and 4 parsecs are very different things. In our case, the data over which we obsess usually comes expressed in currency, our society's universal unit of accounting. We give this many dollars of humanitarian aid; we invest this many in a political campaign; we do that many dollars in environmental damage every year, and so on.

On a purely metrological level, this universal unit itself exposes our rationality as a farce. No one would use feet if the feet-to-meter exchange rate were constantly in flux, because it'd be a bad unit, but we decide to value actual material things in terms of dollars all the time. We value whales in terms of dollars,2 which is absurd because whales, metrologically speaking, are a much better unit than dollars. Unlike dollars, a whale is always a whale. Many of us have wondered how much a loaf of bread would cost in modern dollars for someone in antiquity, only to search for an answer and find that, actually, that's a meaningless question, because our fundamental concept of money is constantly in flux. Meanwhile, like whales, one loaf of bread is still one loaf of bread.3 By constantly converting everything into dollars, we create arbitrary precision that cannot by its very nature be accurate. It's a process that warps our reality and denies us agency.

The mug at the beginning, in this context, is proof of its owner's conformity, and a warning that those who don't conform will be viewed as social inferiors. As I've argued before, demanding that everything be measurable is not just homogenizing, but inherently conservative, deterministic, and pessimistic. Progress requires hoping for change, often irrationally, because nothing about progress is rational. Had Martin Luther King followed the data, he never would have talked about his dreams, which are famously irrational. You can measure how people feel about another Marvel movie, or a politician they already know, or whether they prefer this version or that version of a product. It's much harder to measure interest in a brand new movie idea, or an unknown politician, or a radically new invention. The bigger the change, the harder it is to measure. Doing new, big things requires that squishy human stuff. It requires stories, not data, because radical change is, by its very nature, immeasurable.

1. In that very same essay, they also identified what I called Cucksumerism (a term Boy Boy coined): "Any need which might escape the central control is repressed by thar of individual consciousness. The step from telephone to radio has clearly distinguished the roles. The former liberally permitted the panicipant to play the role of subject. The latter democratically makes everyone equally into listeners, in order to expose them in authoritarian fashion to the same programs put out by different stations. No mechanism of reply has been developed, and private transmissions are condemned to unfreedom."

2. A shout-out to Adrienne Buller's The Value of a Whale, which I still look forward to reading, for making me aware that people actually think this is a reasonable thing to do.

3. To overcome the inherent irrationality of this unit of value, Marx proposed a labor theory of value, essentially using hours of labor rather than currency as the unit of accounting. Unlike currency, we can figure out how many hours of labor bread was worth in antiquity. Isn't that really what we mean by that question anyway?