Note: This is an extended version of what has proven to be, by far, my most popular post. For the original, click here.

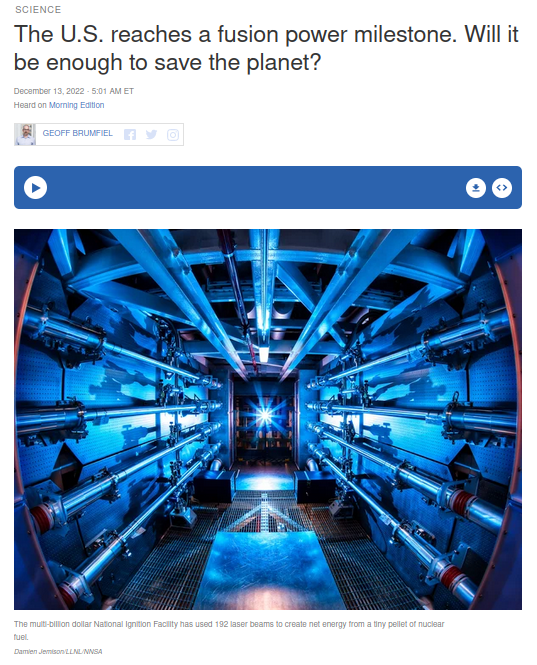

Physicists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory recently announced that a tiny pellet of hydrogen fuel in a fusion reactor has released more energy than the lab’s lasers have put in. NPR has chosen to cover this achievement like this:

NPR has covered several science and technology stories this way, from nuclear fusion to carbon removal to even chocolate and breakfast cereals.

In fact, when searching npr.org for the phrase "save the planet," one comes across two kinds of stories. The first offers a dizzying array of products of all shapes and sizes that are going to save us from climate change. The second looks like this:

The message is clear – NPR expects its readers to be passive consumers of climate change solutions. We are asked to marvel at the shiny innovations brought to us by our technological superiors, and while we wait for them to solve climate change for us, we are given strategies to cope with the stress. Climate Change is thus transformed – or perhaps reduced – from a political problem to a technological one. I propose we name these kinds of technologies Technological Antisolutions.

A Technological Antisolution is a product that attempts to replace a boring but solvable political or social problem with a much sexier technological one that won’t work. This does not mean that we should stop doing R&D. Much like the fusion example, a technology that is worth pursuing can become a technological antisolution depending on its social and political context. The physicists have done nothing wrong and should be congratulated on their achievement; NPR, on the other hand, has devalued their work by placing it in an inappropriate context.

Technological Antisolutions are everywhere because they allow us to continue living an untenable status quo. Their true product is not the technology itself, but the outsourcing of our social problems. They alleviate our anxiety and guilt about not being active participants in political change, and for their trouble, founders and investors are richly rewarded.

In fact, most of the world’s richest man’s wealth has come from precisely this phenomenon. Investors and analysts have long puzzled over the wildly inflated valuations of his companies, noting that Tesla’s market cap has oftentimes exceeded the combined market cap of its five major competitors. It is because Elon Musk does not sell cars, or spaceships, or tunnelling equipment; he sells political apathy. He tells us he can solve our social problems by replacing them with cool sounding technology that he will never be able to deliver.

There is perhaps no better example of a technological antisolution than the self-driving car. American transit is a multifaceted political crisis of astounding proportions. The average American’s daily routine involves spending an ever-increasing amount of their day operating 4,000 lbs of heavy machinery that burns fossil fuel, which is made available via an international supply chain riddled with violence and ecological devastation. Oftentimes, these machines capable of cruising safely at 70+mph are forced to sit in queues miles long because there are so many of them. This twice-daily society-wide masochistic ritual destroys the air quality in our cities, the psychological well-being of its participants, the physical spaces we inhabit, and the only wet rock capable of sustaining human life in an otherwise cold and unwelcoming universe.

We all instinctively know this is madness, and into this breach steps the self-driving car industry. They offer to leave our lives and our cities completely intact. They offer the status quo, but perfected. They offer convenience in exchange for political apathy and patience. Perhaps NPR can give you some tips on how to deal with your traffic-anxiety while you wait for your millenarian deliverance.

Self-driving cars in which you sit in a personally owned consumer vehicle with no steering mechanisms and continue your life as before are a lie. They are not coming. Even those making self-driving cars know it and openly admit it, though they don’t exactly frame it as such. Here’s an excerpt from an article from The Verge, in which Andrew Ng, a prominent self-driving car advocate, discusses the trouble that self-driving cars have navigating unexpected situations:

I asked him [Andrew Ng] whether he thought modern systems could handle a pedestrian on a pogo stick, even if they had never seen one before. "I thinkmany AV teams could handle a pogo stick user in pedestrian crosswalk," Ng told me. "Having said that, bouncing on a pogo stick in the middle of a highway would be really dangerous."

"Rather than building AI to solve the pogo stick problem, we should partner with the government to ask people to be lawful and considerate [emphasis added]," he said. "Safety isn’t just about the quality of the AI technology."

In case you missed it, here’s Cory Doctorow explaining the sleight of hand happening here, citing that very interview:

Using "deep learning" to solve the problems of self-driving cars is a dead-end. As NYU psych prof Gary Marcus told Chafkin, "deep learning is something similar to memorization…It only works if the situations are sufficiently akin."

Which is why self-driving cars are so useless when they come up against something unexpected — human drivers weaving through traffic, cyclists, an eagle, a drone, a low-flying plane, a deer, even some pigeons on the road.

Self-driving car huxters call this "the pogo-stick problem" — as in "you never can tell when someone will try to cross the road on a pogo-stick." They propose coming up with strict rules for humans to make life easier for robots.

That line there at the end is the game. These cars will require physically modifying the environment to make some sort of track and/or forcing human behavior to comply with the needs of the AI, or as Ng put it, having "the government [...] ask people to be lawful and considerate.". Had we spent the $100 billion dollars blown on self-driving cars on a massive overhaul of American public transit, we could have already built the infrastructure we need to solve this crisis. Instead, we have made a few tech entrepreneurs very rich, and we are left with the same political problem as before.

Self-driving cars are not even the only example of a technological antisolution within Musk's own companies. SpaceX promises perhaps the dumbest solution to climate change possible: colonizing space. Elon Musk has convinced legions of people that it will be easier (or maybe better? more desirable?) to colonize Mars to save humanity than to avoid destroying the only planet where food literally grows on trees and water falls from the sky.

Leaving Musk, but staying on our rapidly deteriorating home planet, there are companies such as Inter Earth that promise to sequester carbon from the atmosphere by "pickling" trees, i.e. burying them in salt marshes so that they will not decompose. Kodama Systems is also burying trees underground, and they have raised $6.6 million from Bill Gates's climate investment fund along with other investors. These "biomass burial" technologies make their money by selling carbon credits for the wood that they cut with chainsaws, load onto trucks, haul to pits dug with heavy machinery, and finally bury, thereby absolving polluters of their own emissions.

Here, some readers might object to calling "biomass burial" a technological antisolution. How can putting trees in holes qualify as technology? For our purposes, we shall sidestep the question of what qualifies as a technology by deferring to the company itself. This is perfectly illustrated by Kodama’s own website, including its very domain: "kodama.ai." Their marketing copy reads as follows:

Recall that a technological antisolution depends not so much on the technology itself, but its social context. Kodama Systems is clearly presenting itself as a technology company. Its capital comes from no less a technologist than Bill Gates. The website and marketing copy say it is a technology. Regardless of the technological merits of throwing wood in holes, it is, for our purposes, a technology.

I want to be careful here. I do not doubt that Kodama Systems employs many qualified foresters, researchers, scientists, engineers, ecologists, and/or others with a sincere and laudable commitment to mitigating climate change; nor do I doubt that some of their projects do actually have a positive impact. A similar thing is probably true for many of the companies mentioned in this piece. The criticism here is aimed not at the people in these companies, but at a society that is incapable of channelling their abilities and desires to help without repackaging their mission into something monetizable and frankly absurd. Foresters at these biomass burial companies are incapable of funding their work protecting our forests without raising money from capitalists such as Gates; the viability of their work as a business relies on selling carbon offsets to the very polluters most responsible for the climate crisis in the first place.

This is the process by which technological antisolutions often come into being. In our world, doing things requires money. Those ever decreasing few with most of the money generally prefer to avoid political change. Those who wish to do things are therefore forced to take on the aesthetic of technology in order to attract capital. They must make bold, futurist technological claims, while carefully avoiding political ones. Technology is good for business; political change is usually less so.

This is why lurking under most social problems lie so many companies offering technological antisolutions. Take the American mental health crisis. That a rapidly increasing number of Americans are miserable is as pure a social problem as can be. Danielle Carr has recently very persuasively argued this point in the New York Times:

But are we really in a mental health crisis? A crisis that affects mental health is not the same thing as a crisis of mental health. To be sure, symptoms of crisis abound. But in order to come up with effective solutions, we first have to ask: a crisis of what?

Some social scientists have a term, "reification," for the process by which the effects of a political arrangement of power and resources start to seem like objective, inevitable facts about the world. Reification swaps out a political problem for a scientific or technical one; it’s how, for example, the effects of unregulated tech oligopolies become "social media addiction," how climate catastrophe caused by corporate greed becomes a "heat wave" — and, by the way, how the effect of struggles between labor and corporations combines with high energy prices to become "inflation." Examples are not scarce.

For people in power, the reification sleight of hand is very useful because it conveniently abracadabras questions like "Who caused this thing?" and "Who benefits?" out of sight. Instead, these symptoms of political struggle and social crisis begin to seem like problems with clear, objective technical solutions — problems best solved by trained experts. In medicine, examples of reification are so abundant that sociologists have a special term for it: "medicalization," or the process by which something gets framed as primarily a medical problem. Medicalization shifts the terms in which we try to figure out what caused a problem, and what can be done to fix it. Often, it puts the focus on the individual as a biological body, at the expense of factoring in systemic and infrastructural conditions.

If reification is the process by which political arrangements become technical problems, then technological antisolutions are Silicon Valley’s response. Our social problems are solved by discrete monetizable apps, screened by the App Store’s "high standards for privacy, security, and content," for which Apple charges an exorbitant 30% cut of in-app revenue.

This is how, in the wake of ChatGPT-fueled excitement about AI, NPR came to run the following story:

The story focuses on Wysa, an app that provides mental health therapy via AI chatbot. According to NPR, Wysa's "chatbot-only service is free, though it also offers teletherapy services with a human for a fee ranging from $15 to $30 a week; that fee is sometimes covered by insurance."

Automated therapy is obviously a bad idea. In a post-lockdown world, with the rampant loneliness that came with it, the tacit admission that no single human being of the 8 billion on the planet actually cares enough about you to help you is nothing short of devastating.

What’s more, if current AI is poorly suited for the unknowns of driving a vehicle – a comparatively simple task – how can we expect it to navigate the minefield of the entirety of the human experience? As far as I am aware, no technology has ever experienced the simple pleasure of a purring cat, the smell of fresh bread, the joy of live music, or the grief of losing a loved one. Virtually every human has, yet even with the wealth of shared life experience allowing us to connect with our fellow humans, we require our mental health professionals to undergo additional rigorous training and certifications. Wysa expects us to believe that its AI chatbot can do the equivalent of a human being with an advanced degree, meanwhile all the money in the world cannot make technology that surpasses the driving capabilities of a teenager. In fact, it expects us to believe that "[t]he emotional bond people build with Wysa is as deep as that with a human therapist."

Despite all this, Wysa has raised $30 million in venture capital and received uncritical media attention.

With these examples in mind, let us better define a technological antisolution. I propose that for something to be a technological antisolution, it must meet the following 5 criteria:

- It claims to solve a serious social or political problem.

- It is intrinsically incapable of addressing said problem.

- It is profitable under current market conditions.

- It further entrenches existing power structures.

- It is sexy.

The first criterion is straightforward, so we will begin with the second. A product can be intrinsically incapable of solving a problem in a variety of ways. In the introduction, I used fusion as an example of a technological antisolution for climate change. I did that not because fusion is some lie or conspiracy, but because its practical applications are much too far away to "save the planet." According to the Washington Post, a fusion plant prototype – that is just one single experimental plant – is optimistically a decade away.

That same Washington Post article contains the following quip:

For decades, scientists have joked that fusion is always 30 or 40 years away.

Those of you who follow tech news will probably recognize that joke, because it is also often repeated about self-driving cars (though with typical Silicon Valley hubris, the number given is usually reduced to 5). This is a relatively common joke format in the technology world, and when encountered, should give readers a hint about the kind of technology being discussed.

Technologies may also fall afoul of our second point by failing to actually address the problem. Climate change is caused by the burning of fossil fuels, not by a lack of subterranean trees. Allowing companies to continue to pollute on the condition that they pay to have trees buried doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. Instead of reducing our energy usage and/or moving to alternative forms of energy, we have constructed elaborate schemes to justify the continued burning of fossil fuels. It should come as no surprise that these schemes specifically designed to absolve polluters of responsibility for the problem are coming under increasing scrutiny by researchers for systematically overestimating carbon offsets. In other words, it seems the system designed for the benefit of those who burn fossil fuels is benefiting them even more than we had hoped.

In fact, the very creation of these carbon markets gives us the purest form of our third criterion. Burying trees in salt marshes is not normally considered an economically productive activity. In the case of climate change, the situation is so dire that, in order to protect itself, global capitalism has conjured one of the necessary criteria for technological antisolutions out of nothing. It has done so to ensure its continued viability because of our fourth point; by buying carbon credits, the world’s largest polluters not only greenwash their brands, but they also become the main benefactors of environmental projects throughout the world. Many conservation projects now rely on the existence of carbon markets for funding, inextricably and perversely linking the supposed solutions to climate change with the perseverance of the status quo.

Carbon markets are a bit of an exception. Usually, the conditions for profitability already exist. Even I will gladly admit how much I want a self-driving car. Likewise, in the case of AI therapists, healthcare is a lucrative industry. There is a huge unmet demand for mental health services, which Wysa seeks to address by selling AI therapy to employers, making happier, more productive employees. After reading their dystopian marketing copy, one might argue that reenforcing the existing power structure is their explicit goal:

SpaceX provides us with the perfect example of our final criterion. Looking up at the stars and being filled with wonder is a universal human experience. Some 5,000 years ago, our ancestors dragged giant rocks 160 miles to line them up with stars on a particular hill. The details as to exactly why are lost to time, but the basic gist is clear enough – space is awesome. Likewise, robots, fusion, and AI are all exciting. Biomass burial specifically might not be the stuff of science fiction, but saving the planet from an existential threat certainly is. SpaceX spells this out very explicitly in their "Mars & Beyond" marketing copy:

"You want to wake up in the morning and think the future is going to be great - and that’s what being a spacefaring civilization is all about. It’s about believing in the future and thinking that the future will be better than the past. And I can’t think of anything more exciting than going out there and being among the stars."

-Elon Musk

That is a quote from Elon Musk, until recently the world’s richest man and perhaps our society’s most preeminent technologist, openly admitting that his entire mission to colonize Mars is all about the vibes. It is a perfect encapsulation of the hollow promise of technological antisolutionism. That SpaceX places such a stupid quote so prominently on their marketing material is damning, but also underscores the importance of the fifth criterion. Technological antisolutions have to be fun to work on and talk about; otherwise we would not fall for them.

No one wants to write articles about maintaining snow plows or the routine structural assessments of bridge pylons – we want to talk about robots. This is the appeal and the danger. Antisolutions offer us just enough purchase to envision a better world, distracting us from the bleak reality that our society is stagnating. We can barely maintain the infrastructure that previous generations actually had to go out and build, much less imagine a world where we expand it. It is unthinkable to the average American living in Manchester, NH or Columbus, OH that the town would break ground on a new subway system. In the few cities old enough to have a subway – itself a damning concept if you stop and think about it – even upgrading the rolling stock when the existing cars are past their end of service date seems an impossible hurdle to overcome. As our society becomes increasingly unable to fathom tackling its complex political problems, more companies offering technological antisolutions will step in to monetize our inaction and discontent.

On first glance, it may seem the very phrase technological antisolution implies the existence of its opposite, the technological solution; that there is the right startup for every problem. In this way of thinking, antisolutions are something like a misstep in the otherwise unerring and inexorable march of technological progress.

Our society has trained us to view technology as a linear progression of quasi-divine revelations – first there were clay tablets, then paper, then the printing press, and so on until eventually Apple removed the home button from the iPhone. Those who dislike the removal of the home button are derided as luddites, stubbornly refusing to adapt to a world constantly being improved by our most exalted technologists.

This is not a productive framework for creating and understanding technology. It concedes a top-down model, in which technology is narrowly defined and created by specialists. Regular people are not participants but simply observers and consumers. This model is contradicted every single day, when millions of people use a variety of technologies to do the many jobs that keep our world operational. These technologies vary from on-site improvisations to fully autonomous tractors, and are often made, maintained, and/or modified by the very workers that use them. Their ingenuity, from ratchet straps and zip ties to elaborate custom fabrications, is a daily testament to our collective participation in technology. Companies are actively attempting to lock us out from modifying or even repairing their products, a tacit admission of the inherently participatory nature of technology they seek to supplant.

So perhaps we should take a moment to examine this accusation. What is a luddite?

The Luddites were textile workers. In 1812, Ned Ludd, from whom the Luddites take their name, wrote that "framework knitters are empowered to break and destroy all frames and engines that fabricate articles in a fraudulent and deceitful manner and to destroy all framework knitters’ goods whatsoever that are so made."

They destroyed machines not because they hated textiles or automation, but because machines were being used to rob them of their livelihood, or as they put it, "in a fraudulent and deceitful manner." The Luddites understood that any piece of technology is intrinsically neither good nor bad. Instead, what matters is its social context. In the case of the Luddites, technology meant poverty, so they destroyed the technology.

In the two centuries since, the term has become derogatory, evidence of a dominant technocratic worldview that understands technology as the prime mover in our society, regardless of its human cost. I propose we reverse that relationship. Social and political progress should drive technology, not the other way around. When faced with complex problems, we should not assume there is a technological solution. Instead, we should ask ourselves to envision a better world, and then decide what technologies, if any, we need to get there. When technologies crop up that do not fit our vision of a better world, perhaps then we should remember the example of the Luddites.