Apple recently released, and subsequently apologized for, a commercial for their new iPad, in which a giant hydraulic press crushes every symbol of human creativity that they could fit on a screen, starting with a trumpet. When the press comes back up, it reveals a single iPad, their thinnest version yet.

If you're a well-adjusted person, it's intuitively obvious that this commercial might be poorly received. People really like music and art. It's tone deaf (pardon the pun) to crush the tools that we use to produce the things we love, then substitute them with your product, but that's only the surface. Going deeper, it's emblematic of the increasing tension between tech companies' vision of the world and what anyone would want, a trend that will only continue as they reach further into our personal lives.

Not coincidentally, as I'll soon argue, it also provides us with an apt metaphor for the process of writing software. Computers can only do exactly what they're told, so developers have to decide what to tell them. Anyone who has ever tried to explain their job to a new trainee knows how hard this can be, but trainees are human beings, able to intuit missing pieces, ask questions, etc. Since it's prohibitive to rigorously describe literally everything to a computer, we have to simplify, or maybe even, metaphorically speaking, flatten.

If the tech industry limited itself to forms, calendars, and so on, then this wouldn't be so troubling. It's often even desirable. After all, I'm actually quite busy when I'm at work, and I want my various work tasks to be well-defined and streamlined to keep them manageable. Computers are good at this kind of simplifying, in part because they force us to rigorously formalize these processes. But the press in the commercial didn't crush rolodexes, appointment notebooks, and filing cabinets; it crushed musical instruments. Work and music are different. Seen this way, the outrage at the Apple commercial is outrage at the incursion of this workplace mindset, which is itself deeply enmeshed with the nature of computers, into our personal lives, for which mobile devices are the vanguard.

Before, when we left work, we entered a part of our lives in which we no longer had to comply with rigid and formal tasks. I don't make music to make as much music as possible as cheaply as possible. Music is a form of self-expression, and self-expression is in tension with rigorous formalization. If every work calendar invite was like a marriage invitation, with the font fussed-over and printed on decorative stock, organizing meetings at work would be impossible. Conversely, receiving beautiful, highly-personalized invitations might be inefficient, but I don't want it optimized.

This tension becomes more pronounced the deeper these systems reach into our personal lives. Setting aside its desirability, it's much easier to formalize work tasks than it is to formalize a band. The uniqueness of each member, as well as the uniqueness of their relationships, is often what makes a band so wonderful. At work, functional relationships with our coworkers can often withstand this kind of treatment, but only because the relationships exists to accomplish a goal. In my personal life, the relationships are often the point. A relationship with a partner is very different from that with a coworker, bandmate, or neighbor, but even relationships within each of those categories are extremely difficult to explain in their entirety, even to other humans, much less in the mathematically precise terms necessary for computers to understand them.

As usual, dating apps are the most extreme example of every pathology in the tech industry. They've formalized and systematized a process once mediated by overlapping networks of human relationships, which is even more complicated than a single relationship. It would be an impossible task to create a dating platform that could somehow take into account the vast complexity of human courtship, not to mention how hopelessly inefficient these organic dating schemes can be.

There's also an irony here. Dating apps reject the inherent complexity of human relationships, but they also exist for the sole purpose of mediating human relationships. They literally don't do anything else. There are many tasks that a so-called dating app could conceivably do, like, say, book you a nice dinner reservation, or find you museum tickets. Instead, they're exclusively algorithmic middlemen in human relationships. This is a natural point of leverage in a society, where companies can get the most power for the least effort. It positions them well to play all sorts of games with us, the details of which we've discussed elsewhere.1 Users then must adapt to these changed relationships, shaped at least in part by the companies' needs to make human activity legible to computer systems, and they have done so extensively. The details2 aren't particularly important to us here. What matters is that people change their IRL behavior to comply with the needs of software running on their phone, written by faraway developers.

In a sense, dating apps are what happens when work breaks containment. Work colonizes a part of our lives that once wasn't work, and then rearranges our previously-not-work task to look like a work task. I propose that we call these kinds of systems capture platforms. Capture platforms...

- ... exclusively manage people, but don't do anything else.3

- ... are made possible by mobile devices, which grant companies intimate access to everyone.

- ... formalize previously informal, socially-mediated activities.

- ... encourage "rational" (i.e. selfish) behavior, often by mediating relationships with opaque algorithms.

Dating apps are an extreme example, but there are many others. Couchsurfing was once a non-profit that connected travelers who needed a place to crash with people who had, as the name implies, a spare couch. Couchsurfing wasn't a capture platform, but Airbnb certainly is. It doesn't operate any hotels in its own right, but mediates between hosts and guests. By replacing the friendly and more altruistic logic of its predecessor with the profit motive, and formalizing the relationship into an economic arrangement, complete with reviews, a check-out time, etc., they took a pre-existing idea and converted it into a capture platform. As a result, they swiftly took over, growing so much that Barcelona is banning them because they're cannibalizing cities' housing stock.

Uber is, of course, also a capture platform. They do "ride-sharing," meaning that they formalize the once informal activity of giving someone a ride. This is distinct from being a taxi company, which requires owning physical taxis, a messy business. It's much better to simply connect drivers to riders, and focus all efforts on developing complex algorithms designed to manage those relationships in the most lucrative way possible. Uber, as with many of the so-called gig economy companies, emphasizes that these gigs are not jobs, but rather a hustle that one can do outside of their regular work. This is a common result of the third feature of capture platforms: In formalizing previously informal activities, they often ask us to turn leisure time into work time and hobbies into hustles.

More concerning still, capture platforms seem to be an attractor in the space of tech companies. Consider the example of Amazon: They started in 1994, selling books, which they warehoused and mailed to you. By 2000, they opened their "marketplace," in which Amazon mediates between buyers and sellers. Today, 60% of Amazon's sales were third-party marketplace sales, up from 54% just 4 years ago. Amazon is, in theory, the opposite of a capture platform: They very carefully manage the international logistics of stuff. That even they are increasingly heading in this direction is a testament to the attractive power of the model.

As increasingly large parts of our lives come under the influence of capture platforms, we reorganize our individual behavior around their design. Someone who starts driving for Uber might buy a nicer car, hoping to expand their not-a-taxi business. This makes them more vulnerable to Uber arbitrarily "twiddling" with their price algorithm, something that they're well positioned to do because Uber knows that user bought that car, as well as basically everything else there is to know about that driver. Likewise, someone might decide to build an additional apartment in their house to rent out on Airbnb. These aspiring entrepreneurs are starting a business entirely dependent on the whims of an unaccountable company. No one would enter into an adversarial negotiation with, say, a potential employer, and just divulge everything that the opposing party would wish to know, but the situation here is identical.

These individual changes add up, creating emergent social ones. Some are obvious, like how restaurants have been forced to change their business to accommodate the gig-economy delivery model, whether they want to or not, but others are more subtle. Because these platforms manage exclusively people, and never things, they're agile. When kerosene replaced whale oil, whaling companies, having invested so much capital in whaling equipment, used whale oil to make margarine. Capture platforms, by definition, can never be left holding the bag, because they offload those capital investments onto their hosts, sellers, or drivers. They're structured so that others will hold the bag for them, leaving them free to adapt to new situations.

Capture platforms have reshaped parts of our lives that, until very recently, would've been considered way out of reach for a tech company. Consider this reddit post, in which a husband asks a wife to open up their marriage. I chose this topic because it's as intimate a topic as I can imagine. Here's how the wife reacts:

I was distraught the whole day and later that evening I downloaded tinder. I uploaded one of my least flattering pictures. Wrote that I’m a mother of 2, and that I was in an open marriage. I showed my husband my profile. After one hour I got over 100 mayches [sic]. Next day it was around 2000. My husband got very angry and demanded I deleted the app. He said he got the point and to forget about it.

Before we get into it, here's one more, in which the couple did go through with it, but closed it after she had much more success on Tinder than he did. Here's part of the top comment:

Classic story of a straight man way overvaluing himself in the dating market in an open marriage. I’ve been in open and closed relationships, offered my ex-husband an open marriage, and 95% of the time straight men want it until they experience it ....

This is such a common trope that there's an entire subreddit dedicated to it. Most of these stories hinge (pardon again) on the dating app user experience, and how it's different for men and for women. Regardless of your feelings about open marriages, this is a lot of power to give to a tech company. Until very recently, their presence in such a private matter was unimaginable, but now users discuss the "dating market," a term4 that hints at the selfish user behavior on capture platforms, and Tinder as one and the same. This also underscores the fourth feature of capture platforms: Algorithms can simulate the experience of living in a market, while actually being carefully planned to favor the platform. Markets are supposedly emergent, relying on the price mechanism to distribute the necessary information of supply and demand in a decentralized manner, but algorithms are quite the opposite: They're centralized and planned. A single source disseminates all information. Still, despite being opposites, the subjective experience of both can often be the same: We're subject to obscure forces outside our control that only technical experts could even begin to understand. This allows capture platforms to hide in plain sight. We're all preconditioned to accept these kinds of undemocratic conditions. Capture platforms know that, and sometimes even lean into it, calling their platforms "markets" when they in fact carefully control the dissemination of all information between participants.

If you read enough of these reddit stories, it starts to feel like dating apps are defining what kinds of relationships are allowed, and, whether consciously or not, punishing deviation. Since dating itself is no longer distinguishable from dating apps, Tinder's heteronormativite experience becomes rigidly codified and perpetuated. Couples wishing to chart their own course must contend with friction when they deviate from their pre-defined roles.

This power, not just to surveil us in our most private moments, but to shape our most intimate conversations, up to and including determining the details of our marriages, gives great normative power to tech companies' conceptions of their users. Companies can and should be pressured to take a more nuanced approach: They should be careful to avoid gender stereotypes about users, or more carefully examine these excessively Taylorist assumptions of human nature, but such calls are in conflict with the needs of the tech companies themselves. To write computer programs, developers must make flattening assumptions about tasks and people in order to keep the code manageable. Each simplifying assumption is also simpler and more easily maintained code because computers are stupid and need everything spelled out in detail. It's only a small jump from the need to formalize to, say, trafficking in gender stereotypes. Likewise, assuming that users are little factory workers that want to do tasks as quickly as they can, even when they're, say, dating, is a powerful simplifying tool. It gives license to throw out complexity whenever possible, under the guise that it's what your users want. If people can be reduced to five pics, a bio, and a few dropdowns, then it becomes easier to store their data, search it, design interfaces around it, and so on.

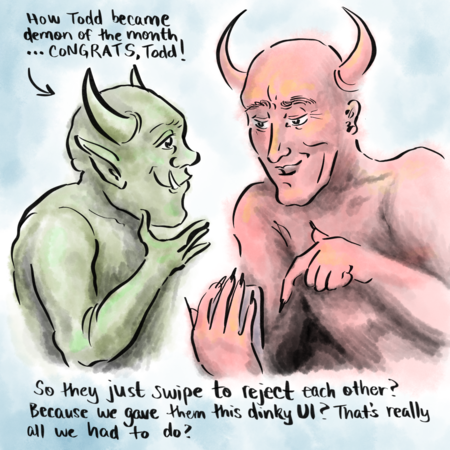

In other words, capture platforms are more than just bad behavior from bad actors, though they definitely are that: They're part of a feedback loop. If tech companies wish to push deeper into our lives, which they must do, because the line must go up, they need to formalize human tasks that are increasingly undesirable to have formalized. Then, backed by infinite capital, they establish themselves in previously unadulterated human activity. Complexity doesn't scale, so they make further simplifications to the human activity, until the entirety of human courtship is collapsed into swiping left or right at a single picture. Because, as we all know, established tech platforms are impossible to dislodge, they become naturalized, even if everybody hates it.

We can see evidence of this cycle not just in the platforms, but in how tech companies talk about users. Many product teams at tech companies create "user personas," fictionalized composite characters with names and backstories that act as stand-ins for their users, conveniently documenting exactly this. Here is the very first persona on the very first result when I search for "user persona examples."

Persona example 1: Jannelle Robinson, PhD student

Description: A busy PhD Student who needs a quiet place to study and read without distractions. She spends a lot of time on campus, refuels often and is a major coffee lover. She is the ideal customer for Julia’s Cafe. She wants to receive quick and professional service; order online from her smartphone to avoid lineups, and not deal with over-conversational staff members.

Every single one of the top 5 results had at least one example with the word "busy," and even those that don't explicitly say as much clearly imply it. Here's another example, this one from Hubspot's blog:

Name: Rachel

Description: Rachel cares most about her career, her appearance, and her social life. She loves to get ready for her day but doesn’t enjoy the amount of time it takes to put on her makeup and fix her hair. Rachel is most interested in products that can make her life easier or help her save time.

Hubspot gives us 7 examples. 4 are women, and 3 are men. None of the women are older than 35 (22, 25, 25-34, 35), and none of them men are younger than 40 (45, 40, 58). All 3 men own their own businesses, whereas none of the women do, at least not explicitly, though I'm not sure which of those options is worse.

Unfortunately, I can't do a rigorous survey of user personas of the industry, because they're normally internal documents, but I did read as many of them as I could find,5 and I have some hypotheses. I suspect that the closer a tech company is to being a capture platform, the more "busy" the descriptions of users become. This is not a quality of the users as such, but an assumption that tech companies must make to justify the necessary flattening of human tasks that keeps the software implementations manageable. It's simply not possible to write software that understands most human tasks, so we need people to be too busy to do those tasks to justify our decision to simplify them. Users, who don't even have the time to sit and enjoy a coffee, don't want to bumble (pardon yet again) their way through these time-intensive human rituals, going with friends to parties to meet someone, or being set up with roommates. They'd rather quickly run through 30 potential candidates from the convenience of their phone, where they can evaluate as many potential matches in a single minute as it once took them months to do.

Organizations that aren't interested in re-organizing non-work tasks for profit don't have to do this. I put out a call on Mastodon for examples of user personas, and many people responded (thank you!). It turns out, perhaps unsurprisingly, that the people who follow me are way cooler (and better looking) than most people, so they work on cool stuff. The examples that I got from them were of government contractors, mission-driven initiatives, open source projects, and so on, and not one wrung their hands about how damn busy all their users are all the time. Instead, I read sober attempts by serious people to categorize their users and enumerate their various needs.

This brings us to the fundamental tension: So long as our computer systems are accountable only to market forces, capture platforms will remain a popular business model, no matter how bad they are or how much we hate them. Modern devices give companies so much access to personal information, and modern computing makes it so easy to fiddle with that data continuously, that companies forever looking to cut costs are going to prefer to give people platforms to do things and micromanage them rather than do things themselves. Rearranging the way that we date and converting housing into short-term rentals are just side effects. Given the opportunity, companies prefer to rearrange human life in a way that suits them, rather than do what's best for us. This is a well-known phenomnenon, with examples ranging from union-busting, to corporate lobbying, to environmental degradation. It should be no surprise that, given new tools, they'll find new ways to do the same thing.

Aside from overhauling our entire economy, which we should do now, otherwise the earth will do it for us, what else can be done? I'd argue that we should start thinking about and experimenting with what post-capitalist software might look like. Using the same logic of capture platforms but in reverse, a dating app might not be so bad if it augmented rather than supplanted human processes, accepting that human interactions aren't a means to an end, but an end of themselves. Maybe they should strive to make the process of dating more fun, rather than more efficient. I'm temperamentally unsuited to brainstorm the specifics, but I could imagine a scenario in which two people meet at a party and decide to scan a QR code, connecting on an app that is supposed to help them do fun things, rather than mediating who they could talk to and when.

For more concrete inspiration, we could return to the example of Amazon. Setting aside its many, many other problems, Amazon is, in theory, a great use of computers. There are so many things in the world, and we need to keep track of them until they get to the right person. Using computers to help organize this task is a great idea, and, crucially for our purposes, doesn't require codifying rigid ideas about who a person is or ought to be. In the platonic form of an Amazon-like service, the idea of a person is left open-ended, whereas the various processes and things that it tracks are rigorously formalized such as to eliminate errors and waste. As we introduce more assumptions about what a person should be, in the form of targeted advertising, or breaking up people into classes of buyers and sellers, and so on, our Amazon-like system starts displaying more and more symptoms of capture platforms, until it eventually converges on an algorithmic pseudomarketplace that mediates between buyers and sellers.

Acknowledgements: I read a lot of stuff for this one. The word "capture" in "capture platform" comes from Agre's Surveillance and Capture. Much of the idea behind them and their ability to normativley define user behavior comes from there. I leaned heavily on some of his discussion on formalization in "Conceptions of the User in Computer Systems Design," a chapter in this book.

I also read Joanne McNeil's book, How a Person Became a User. I didn't take any particular idea from the book, but its influence helped me turn what was a pretty disorganized series of notes into something coherent. The book is also a joy to read, in part because it's well researched, but also because she's a fantastic writer. I was excited to learn that she also writes fiction. Here's her site.

Finally, some of capture platform was influenced by Nick Srnicek's idea of "lean platforms" in Platform Capitalism. Srnicek's lean platform is one that takes the idea of outsourcing to its natural conclusion, carefully avoiding actually owning or doing anything, distinguished from "product platforms," as well as various other kinds. I found that to be a helpful starting point, but I was more interested in how these platforms interact with human beings through computers.

2.. Reddit is full of these discussions, some of which are depressingly sophisticated and include entire primers on statistics. Here's a few examples:

- https://www.reddit.com/r/Tinder/comments/11fi6z9/the_ultimate_tinder_guide_part_i/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/GameGlobal/comments/fuz5hu/how_to_really_succeed_at_tinder_not_just_another/

- https://old.reddit.com/r/seduction/comments/qug2k2/my_strategy_for_tinder_and_bumble/

3. Borrowing here from a common Marxist idea that socialism should "replace the government of persons by the administration of things," a phrase that I've always found a pleasing slogan. It apparently has a complex history, of which I'm entirely ignorant.

4. According to Google Ngrams, the term "dating market" basically didn't exist until it took off in the 2000s. It's a testament to the hegemony of markets that it's the only description that we can imagine for any collective or socially mediated process. Alternatively, it's a testament to the most malignant individualism that people actually think of dating as reasonably like people exchanging goods and services hoping to each maximize their own utility, often at the expense of the other.

5. I read at least a hundred of these. A few more examples: Here's a blogpost that constructs some Airbnb users. Daya is a housewife who is "too busy" and "forgots [sic] to pay bills on time which results in panelty [sic]." Shirley likes to host dinner parties when "she can find the time." Mailchimp's Eliza is "busy," and both their examples are "smart," because of course they are; they're users of excellent taste. They're also universally good-looking, judging by the photos that these companies use. Examples like this are endless. I also want to note that I ran into many LLM-generated articles in this research, like this one.

6. Unsurprisingly, there are no dads.