This post was greatly influenced by Dodds et al's Ousiometrics and Telegnomics: The essence of meaning conforms to a two-dimensional {powerful ⇔ weak} and {dangerous ⇔ safe} framework with diverse corpora presenting a safety bias. The axes used in this post are roughly based on their axes of "power," "danger," and "structure." The post was also partly inspired and influenced by Ran Prieur's TechJudge.

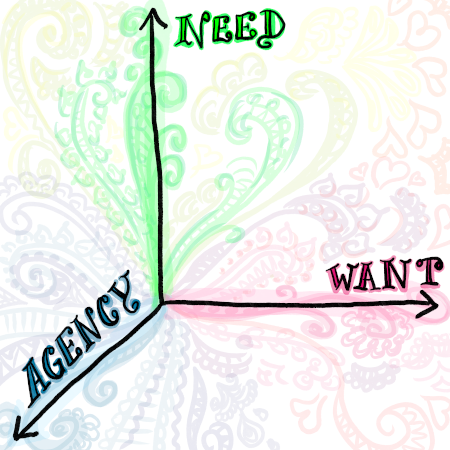

Consider a three-dimensional space with the following three axes: "need," "want," and "agency." Let's go through a few prominent genres of digital technologies and see where the user experiences, seen from the users' own perspective, land in this space. We'll start with a digital technology that people generally like, video games. We don't need video games, but we really want them, because they're super fun! This is a massive oversimplification, but most games work by making a set of rules that players have to follow, often taking the complexity of the real world and boiling it down to simpler game mechanics. In other words, they reduce agency. So, many video games are high-want, low-need, and low-agency. Some video games do have remarkably open worlds, uppping the agency, but they still generally have pre-defined quests, tasks, storylines, etc.

Many productivity apps, like calendars or file-sharing services (Dropbox et al), are high-to-medium-need, low-want, and low-agency. Using them is the digital equivalent of eating your veggies. We use them because they're good for us, not because they're exciting or enticing. Though they're boring or even tedious, they're generally not particularly damaging to the psyche. Likewise, low-need, low-want, and low-agency experiences are, by and large, similarly harmless, though they can be a waste of time if someone is forcing you to use them.

Staying in the low-need and low-agency quadrant, but upping the want, we start to find what's often called "content." It's stuff that you consume. That's where this blog lives, hopefully at high-want, along with weird concept websites like this website, or this one, or this one, or this one, as well as more "normal" stuff, like Tweets, YouTube videos, Reddit posts, etc. Though certain instances within this octant are indeed very harmful, its general user experience is not. In other words, though many individual videos are very bad, videos themselves are fine.

Now consider a universally hated genre of digital technology, online dating. There is no greater human need than the love of other humans, and we desperately want it, so it's a high-need and high-want experience. To examine agency, let's look at the design of the most famous dating app, Tinder, the mechanics of which most platforms have copied, at least to some degree. Tinder users fill out a short biographical profile with a few pictures, then the app presents a sequence of other users' profiles in a sort of slideshow that looks like this (photo taken from Tinder's promotional materials):

Users can then "swipe right" (or "like") if they like this user, or "swipe left" (or "nope") if they don't. If two users both swiped right, then they're "matched." Crucially, users have very little control over who they see, or what order they see them in, outside a few parameters (gender, distance, age, ...), which Tinder explicitly says that it takes into consideration but might ignore. For users, this is a very low-agency environment.

Let's set that aside for a moment and consider a more nuanced digital technology, so-called "ride-sharing" (Uber, Lyft, etc.). Uber et al have two classes of users, drivers and riders. Transportation is important, so for riders, this is a high-need and high-want application, but it's also incredibly convenient. Riders can be picked up at any time, anywhere, with just a few clicks on their phone. That's very high agency. For drivers, this is their job. Jobs are high-need. Flexible jobs where you're ostensibly your own boss (as the gig economy advertises itself) are also high-want, but driving for Uber is, the promises of the gig economy notwithstanding, extremely low-agency. Despite Uber's infamous, blatantly illegal misclassification of drivers as "independent contractors," Uber drivers are told where to go and when, and their pay is determined through secret means entirely outside their control. So, for Uber, the rider experience is high-want, high-need, and high-agency, but that of the drivers is high-want, high-need, and low-agency.

As we can now see, though it's pretty intuitive, high-want and high-need user experiences are of particular interest. Given high agency, it's easy to see that these experiences can be delightful, even liberating, but user experiences that are high-want and high-need easily turn sour. Sometimes, it's context-dependent: Cars are high-want, high-need, and high-agency, until there's traffic, and then they suck. But digital products are unique in this respect. Unlike physical products, companies that make digital technologies can forever, as Cory Doctorow puts it, "twiddle" with your experience, perhaps helping to explain why so many companies that make physical products are increasingly digitizing them.

Twiddling is the key to enshittification: rapidly adjusting prices, conditions and offers. As with any shell game, the quickness of the hand deceives the eye. Tech monopolists aren't smarter than the Gilded Age sociopaths who monopolized rail or coal – they use the same tricks as those monsters of history, but they do them faster and with computers[.]

As he goes on to describe, Uber purposefully twiddles with their various pay and driver/rider matching algorithms to extract more profit from the drivers while passing more costs down to them. Likewise, Tinder allows freemium-tier users only a very limited number of likes a day, though that number is not fixed, but algorithmically determined, nor is it revealed to the user anywhere in the interface. Instead, users go through their feed, swiping left and right, until they go to swipe right and are suddenly told that they're out of likes. Users then have to wait an arbitrary amount of time (usually around a day but it seems to vary based on a variety of obscure factors) so that they can start the process over again.

Because dating is so unique in how much we both want and need it, it's a noteworthy example. A single week of Tinder Gold is $17; a week of Platinum is $23. These exorbitant prices allow users to buy back a miniscule amount of agency. Users can buy unlimited likes, or see who liked them and match directly, bypassing Tinder's algorithmic queue. They also allow users to have "Super Likes" and "Boosts," two particularly illustrative features. A Boost "allows you to be one of the top profiles in your area for 30 minutes," and with a Super Like, "your profile will be prioritized for the person you’ve sent one to." Much like Uber, whose rider agency is subsidized by Uber's tyrannical control over their drivers, boosts allow users to exercise agency at the expense of that of other users. To return to the car example, Boosts and Super Likes are like if car manufacturers could constantly and arbitrarily summon the experience of traffic, then offer you equally arbitrary deals and subscriptions to get out of it.

Companies mediating between us and things that we both want and need have a lot of power over us, which makes the high-need/high-want quadrant dangerous. As a result, their products are often reversed: Instead of simplifying our access to whatever it is that we seek, they hold it hostage. They play games of algorithmic scarcity so that lonely people will pay $100/month for Boosts and Super Likes, perverse concepts dreamt up by the most vulgar capitalists that have no place in the profound experience of human relationships.

If Doctorow's enshittification is a general trend of digital technologies, then this is the quadrant where enshittfication becomes user abuse. For many, if not most, of these high-value/high-need user experiences, in some form or another, we are the very thing that they're selling back to us. We're social animals. What we both want and need most is usually each other. I don't argue that anyone should stop using Tinder, or Uber, or any of the many harmful tech companies, because in a world where a critical mass of people uses online dating, the social landscape around dating has itself changed. It's the same reason that people can't seem to peel themselves away from Twitter despite its implosive deterioration. I don't think that it makes sense to ask for a personal sacrifice unsupported by any real theory of change.

What I do argue is that, since it's our own collective value, our collective action can reclaim it, and, ideally, our collective ownership over it can mitigate if not end this grotesque behavior, which we've tolerated for too long. It's not cool or normal to make an app that charges people a loneliness tax. No kid dreams of growing up to maximize the value extracted from sad people. Only an industry completely dominated by capitalists whose humanity has long succumbed to greed would even think of such a thing, and users are tired of it. A group of people spontaneously set fire to a self-driving car just this week, a testament to the latent rage towards the tech industry, as Brian Merchant astutely noted in that essay.

Just 10 years ago, the tech industry was universally beloved. People are mad because tech companies are hurting them, in various ways, some direct, and some so diffuse that they're hard to pin down. I hope that this framework can help people articulate the harm and their resulting anger. If you're someone who takes part in design decisions, like I am, I hope that this can be a tool to help you argue against dealing psychic damage to users for profit, but your voice matters a lot more in a workplace where you have real power. If you work for a tech company, whether as an employee or a gig-worker, get organized. Here's a list of tech unions that I got from my friends at the Tech Workers Coalition. If you reach out to any of those organizations, someone eager to help will (probably) get back to you.

There's also a growing movement of platform cooperatives, including an Uber competitor owned cooperatively by the drivers. Before you join a tech platform, be it as a gig-worker or a consumer, see if there's a cooperative competitor. Cooperatives don't have access to capital the way that big tech companies do, so just know that it'll probably be under-funded, and a little rough around the edges.

Finally, if you want to start a business, consider making it a cooperative. Cooperatives cooperate with each other, a radical stance in an economy built on adversity and competition, but it's also our only chance at competing with the bottomless capital of tech companies. I'm a member of a worker-cooperative, and since cooperatives help each other, if this interests you, feel free to contact me. Imagine how much different our digital world could be if the products in it were accountable to the people that make and use them.