It seems money is the problem with (and solution to) everything. Every problem from global poverty to the climate crisis is framed in monetary terms. After studying and working in marine conservation, I was constantly told the problem with nature conservation is that there simply is not enough funding. On a fundamental level, the solution to conservation is clearly not monetary – a tree does not need money to grow. Life does not require a monetary input. Quite the contrary, left to its own devices, life thrives and is self-sustaining. So why have I heard this phrase stated as an undeniable fact?

Conservation by definition is stopping the exploitation of a natural resource. In the current framework, conservation is implemented through the establishment and enforcement of protected areas. Protected areas operate under the assumption that the only way to preserve non-human life is to separate humans completely from it. This limited vision of conservation is the natural extension of a negative Hobbesian view of human nature. Current conservation practice assumes that protection and enforcement are the only ways to halt humanity’s greedy and violent tendencies to destroy non-human life.

Is it really in human nature to instinctively destroy non-human life? Think about the last time you were somewhere naturally beautiful – a mountain, a beach, or even a park. How did you feel? Anecdotally, I have watched adult snorkelers at the beach in a childlike state of joyful curiosity while following a school of fish or seeing something new. Even if we consider more violent interactions with nature (e.g. fishing or hunting), its main attraction is not the violent act of killing, but the experience of being outside and the challenge of catching something so well-adapted to its environment. Hunting or fishing is not mindless violence, but a mindful and patient effort that connects people to mostly lost human values of self-sufficiency and subsistence. Despite this, conservation fully embraces a negative view of human nature, and in that, forgets the true driver of the destruction of life: money. It is in the pursuit of profit and limitless growth that life is unsustainably exploited and destroyed. Innately human values of joyful curiosity and self-sufficient subsistence have been replaced by cold commodification and the imperative for profits.

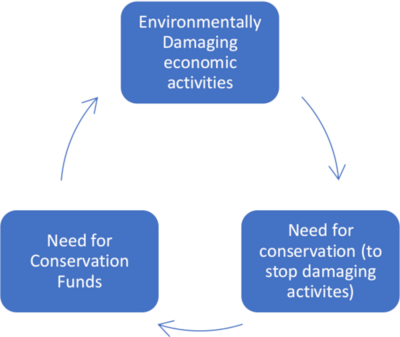

In this pessimistic conservation landscape, conservation requires money to create and enforce protected areas to stop resource exploitation. This presents an ineffective system. On one side, the way to make money is to (either directly or indirectly) exploit natural resources. On the other side, the way we conserve (not exploit) natural resources is to finance protection and enforcement. If conservation requires money, and money requires the exploitation of natural resources, then conservation would require the exploitation of natural resources.

This may not be immediately obvious, so let me present the case study of the carbon market – the most well-established mechanism to channel private sector investment to nature conservation – to explain how the money-centrism of conservation makes it largely ineffective.

Carbon markets take the complex and highly uncertain science of the carbon cycle and selectively simplify it to create an exchangeable commodity – carbon credits. The methodologies used to calculate carbon credits are a source of great controversy, but I will not add to the debate. Instead, I will simply state that in the current context even the most robust methodologies are prone to corruption due to the large demand and little supply of carbon credits, as well as the competitive nature of conservation finance. Project developers are incentivized to quickly meet market demands with questionable scientific and/or social practices or be outcompeted by competitors who do.

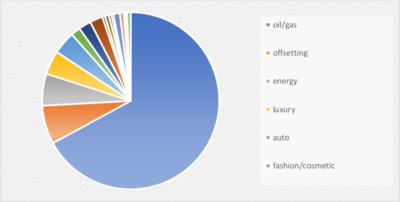

Even if we could somehow make incorruptible carbon markets, carbon markets still reinforce existing power structures. By placing socio-ecological issues in monetary terms, carbon markets place conservation at the mercy of environmentally damaging industries with money. If we take a look at the volunteer carbon market, about 2/3 of all carbon credits issued through the Verified Carbon Standard’s most popular nature-based methodology (VM0007) were purchased by the oil and gas industry. The remainder of the credits were purchased by carbon offsetting firms, or by other socio- ecologically damaging industries – energy, luxury, auto, fashion/cosmetics.

In the current system, conservation relies on environmentally damaging industries. These industries make money through environmentally damaging activities. These damaging activities increase the need for conservation. This increased need for conservation increases the need for money from the environmentally damaging industries. This money-centric conservation system creates an self-defeating feedback loop. Nevertheless, if we judge this system according to the hegemonic economic order of limitless growth, it is actually rather effective. Because it feeds off itself, it will grow indefinitely; it creates more and more economic activity, and increases GDP. Better yet, it can be framed as a conservation victory by allowing more money to be allocated for conservation, even if more conservation funding invariably means more exploitation of natural resources.

In a way, the problem with conservation is money. Not in the sense that conservation requires more money, but in the sense that actually existing conservation depends on the environmentally damaging activities it theoretically intends to mitigate. If there is any hope for life, we must radically change existing growth-focused conservation, and remember the true objective of conservation: to preserve life. We must reject the notion of violent human nature, and question the human-nature dichotomy. We must embrace our joyful curiosity and reframe conservation as the conviviality between human and non-human life. We must stop exploiting nature for economic growth and instead limit our exploitation to meet our subsistence. We must change the subject of conservation from money to life.

Fernando works at the intersection of climate policy, marine conservation, and marine biogeochemistry research. His most recent work focused on seagrass conservation and climate finance. He is particularly concerned with the fatally flawed market based instruments that govern climate change mitigation and ecosystem conservation actions.