On the roughly two-year anniversary of Elon Musk purchasing Twitter, with which he is openly supporting fascism, I want to discuss Jackson, Bailey, and Foucault Welles's #HashtagActivism. The book is a defense of its namesake practice, which they provide through analyzing Twitter data around various social justice hashtags. Readers familiar with previous posts might already suspect where this is going, but I want to begin on a point of agreement:

We push back against the notion promulgated by some that the real work of change only happens offline. Networks and narratives matter, and both are built digitally and corporally. In every era, media technologies have been central to the maintenance of counterpublics and the safe development of counterpublic identity and politics.

It would be ridiculous to argue that what happens online doesn't matter. The rest of this post is going to be critical of their work, but that's because I take them seriously on this point: What happens online obviously matters. We should get it right. Likewise, I agree entirely that, as the authors successfully document, people have used Twitter to push issues of gender and racial justice further into the mainstream. I'm also willing to concede that activism can happen on Twitter, despite my hesitation. This then becomes a question of tactics, and this book is mostly about a specific tactic, "hashtag activism," which they define like this:

Hashtags, which are discursive and user-generated, have become the default method to designate collective thoughts, ideas, arguments, and experiences that might otherwise stand alone or be quickly subsumed within the fast-paced pastiche of Twitter. Hashtags make sense of groups of tweets by creating a searchable shortcut that can link people and ideas together. Throughout this text we use hashtag activism to refer to the strategic ways counterpublic groups and their allies on Twitter employ this shortcut to make political contentions about identity politics that advocate for social change, identity redefinition, and political inclusion.

In their introduction, they present hashtag activism as the successor to Ida G. Wells's radical press, a comparison they make at least two separate times, continuing the tradition of marginalized groups' use of available media technologies. The difference here is obvious with hindsight: Wells's press, as they note, was destroyed by a violent mob. It took an unfortunately common but still extreme act of violence to stop her press because she owned it. Twitter, on the other hand, was purchased legally and without violence by a bumbling yet dangerous fascist clown. Instead of seeing this as activists using the next logical step in linear advances in media technology, it could instead be a dead-end, a sort of Blu-Ray but for activism, and a particularly dangerous one in which some of the most conservative forces in our society convinced people to build movements on a platform that they could buy and control, capturing the networks of solidarity that they built.

This failure to contend with Twitter itself as both medium and intermediary will be a recurring theme of this post. It's a mistake that they make explicitly:

While politicians embed particular issues in opaque language and meaningless euphemisms in their public discourse, ordinary people are able to explicitly advocate using unrepentant and concise rhetoric on these same issues. Notably, Twitter has low financial and technological barriers to entry. Using relatively inexpensive equipment, and with limited technical knowledge, ordinary people can engage in public speech and actions without mediation by the mainstream media or other traditional sources of power. [emphasis added]

That's simply an incorrect statement of fact. Tweets are mediated by Twitter Inc., now known as X Corp., a corporation owned by capital, literally the traditional source of power after which our economic system is named. More broadly, the argument here is one with which readers are already familiar, though they avoid the buzzword: Twitter has democratized discourse.1 When tech companies democratize something, they usually offer convenience in exchange for control, conflating ease of use with democratic participation. In reality, democracy is never convenient. Meaningfully democratizing public discourse would necessarily mean something more profound and transformative than providing a corporate-owned platform that can be bought and sold without any social accountability.

Through this oversight, the book analyzes the content of Twitter while rarely acknowledging Twitter as perpetual mediator. Marshal McLuhan's aptly named The Medium is the Message warns us against doing exactly this:

The content or uses of such media are as diverse as they are ineffectual in shaping the form of human association. Indeed, it is only too typical that the "content" of any medium blinds us to the character of the medium.

Following his guidance, we can reinterpret many of the book's passages accounting for Twitter itself. For example:

Between the 2012 slaying of Trayvon Martin and that of Brown in 2014, Twitter had updated its display features, allowing pictures shared through the platform to be visible without viewers needing to click on a link. This practice increased the number of images shared on the site and directly contributed to the spread of pictures associated with the slaying of Brown. The second most tweeted image among those tagged with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was that of Brown lying dead in the street as Wilson stood over him.

The authors interpret this change as activists innovating on new available technology, but just as valid an interpretation is that Twitter can make arbitrary changes to their platform, to which these activist networks have no choice but to adapt. Twitter is leading here, and they're leading to such a degree that hashtag activism, as a term and a practice, relies on Twitter's branding and the specifics of its implementation, something that their definition makes explicit.

This unaccounted-for omnipresence is probably most pronounced in Twitter's character limit. Tweets are just a couple sentences, and hashtags, worse still, a few words. This extreme brevity exacerbates a problem that Noam Chomsky and others2 have identified:

The beauty of concision, you know, saying a couple of sentences between two commercials, the beauty of that is you can only repeat conventional thoughts. Suppose I go on Nightline, whatever it is, two minutes, and I say Gaddafi is a terrorist, Khomeini is a murderer etcetera etcetera... I don't need any evidence, everyone just nods. On the other hand, suppose you're saying something that isn't just regurgitating conventional pieties, suppose you say something that's the least bit unexpected or controversial, people will quite reasonably expect to know what you mean. If you said that you'd better have a reason, better have some evidence. You can't give evidence if you're stuck with concision. That's the genius of this structural constraint.

When you're forced to be brief, your reader will bring their own context with them. This was true when Chomsky was only given two minutes to talk on TV, and it's even more true of tweeting. The book sees this brevity as a powerful feature, but I argue that Jackson et al don't fully appreciate its implications. On Twitter, not only are users limited to 140 characters, but the surrounding in-app context is ephemeral, algorithmically determined, and highly personalized. When writing or reading each tweet, every user relies on their own personal context from whatever is happening in their life, plus the Twitter-provided in-app context. This has major implications for how Twitters users interact with something as short as a hashtag, but it also means that researchers must attempt to interpret their tweets without access to the relevant context.

To illustrate the depth of this phenomenon and its far-reaching implications for their work, consider the following excerpt analyzing the limits of "digital allyship" through #CrimingWhileWhite, through which users juxtapose police treatment of black and white people.

In these tweets, white users move away from personal narrative, seemingly hesitant to directly compare their more generous experiences with the experiences of victims of police brutality and draconian criminal proceedings and preferring to use high-profile and egregious examples of other white people’s behavior. Here, users call out the unequal application of the law through proxy examples that remove their own experiences from the equation. These contrasting tweets do more to directly engage the larger network of racial justice tweeters by regularly using the #BlackLivesMatter and #EricGarner hashtags, yet they also seem to deflect personal accountability, making white people with extreme privilege the obvious “bad” guys and the police the obvious “racists,” rather than implicating themselves in the problem (or the solution) [emphasis added].

To so precisely interpret the deep-seated intent of a population of complete strangers from such an informal and brief medium is implausible. It very well could be that users are deflecting, or it could be that they are sitting on the toilet, idly scrolling, interpreting the three-word hashtag alongside whatever happens to be top of mind. Then, when they tweet out their own extremely concise message, after which they flush, wash their hands, and never think about that tweet again, the authors are left with a mere 140 characters to interpret. We cannot know why they said what they said, because the tweets are simply too short to explain themselves. What we do know is that, for most people, Twitter is a silly app that they use to kill time, but for the authors, the relations on the app and their implications for social justice messaging are their lives' work. It is with that context that they have interpreted these tweets.

For a simple illustration of what I mean, consider #WhyIStayed. DiGiorno, the frozen pizza company, tweeted "#WhyIStayed You had pizza." This seems innocuous enough, but the hashtag was trending because people were using it to discuss why they stayed in situations of domestic violence. This is a particularly jarring clash of interpretations, one that caused DiGiorno a PR problem, but every single hashtag's meaning is constantly undergoing this pressure.

In more general terms, the extreme brevity of the medium presents two related but distinct problems, both of which are inadequately addressed: First, it directly impacts the efficacy of hashtag activism the practice, as different users constantly read and re-interpret three-word phrases. Second, it poses particular challenges in attempting to reconstruct both what users meant when they tweeted and how others might've interpreted the tweets, making it difficult to, for example, separate some sort of collective intentionality from noise or emergent dynamics of the platform.

These issues, combined with the previously-discussed failure to recognize Twitter's own role in mediating quite literally every single user interaction on the platform, cast serious doubt on any subsequent results. This problem persists throughout the book. Consider the following passage, again related to the above context:

While the other chapters in this book illustrate how decades of mass organizing, activism, and theorizing of racial and gender justice causes by the groups most affected by inequality inform the discourse, reach, and impact of their online networks, here we see the significantly underdeveloped nature of public allyship. In both cases, that of #AllMenCan and that of #CrimingWhileWhite, good intention and a recognized need for change are limited by (1) a lack of nuanced calls for action and systemic political analysis, (2) navel-gazing and performativity, (3) lack of engagement or presence in smaller networks, and (4) the tendency of allyship hashtags to respond to a viral hashtag stemming from a marginalized group, rather than erupting independently and becoming self-sustaining. This pattern results in allyship hashtags being relatively superficial and derivative and thus potentially appropriative of the attention garnered by the group with which their authors hope to be in solidarity.

Compare the above to the following, from earlier in the book, discussing George Zimmerman's trial, and his brother Robert's tweets:

Robert Zimmerman appears in the network because of all the @ replies he received as direct challenges to his contentions about his brother and the story of what happened the night of Martin’s death. In response to a tweet that received less than ten retweets in which Robert Zimmerman said, “Commemorate #TrayvonMartin NE way U like, but don’t slander my brother #GeorgeZimmerman in the process,” dozens of members of the #TrayvonMartin network responded with critiques of the logic of the tweet, critiques of Zimmerman’s general defense of his brother, and pure outrage at the circumstances of Martin’s death. Responses to the Robert Zimmerman’s tweet ranged from “@rzimmermanjr slander? Really?..everytime you speak you r slandering a young man who can no longer speak TRUTH. Murder is murder” to “@rzimmermanjr The Zimmermans think only they have the right to voice their opinions …” and “@rzimmermanjr Man Fuck your brother!” Here we see the interventionist counternarratives that arose from the network in response to the presentation of Zimmerman’s defense, as well as the outrage in the network directed at Zimmerman generally.

One group of tweets gets elevated to the status of "critiques of the logic of the tweet, critiques of Zimmerman's general defense of his brother," and "interventionist counternarratives," while the tweets from the ally groups above were criticized for being insufficiently nuanced, navel-gazing, superficial, derivative, and performative. What makes a tweet performative? How do you measure that from a few short sentences? How exactly do they expect allies to write nuanced systemic political analysis on Twitter? The authors explain:

[A]llyship hashtags that seek to educate members of privileged groups about methods for creating change or about the experiences of those with less privilege are useful to larger projects of political consciousness raising, as are those making demands of particular individuals or systems with power, but if the primary purpose of online allyship is for the privileged group to achieve catharsis, it is not solidarity.

This is one example of a few times that they explain how they've made these judgements, but we find that same problem: They rely on the dubious task of interpreting user intent at scale through Twitter. Their analysis of the networks that allies created does show a difference in how the hashtags are used and propagate when compared to those used by minority groups, but this evidence is far too open-ended to conclusively support such a long list of such specific descriptors of intent. I grant without reservation that most people are insufficiently committed to issues of gender and race inequality, but I also argue that, though they provide some evidence that may support this interpretation, the authors read that context into the tweets and network structures at least as much as they argue the point from source material. Likewise, in the same way that the book judges harshly when it perceives insincerity, the generosity of interpretation that it extends to hashtag activists it finds to be sincere stretches credulity:

#TroyDavis first appeared in my Twitter feed on September 11, 2011—ten days before Troy Davis himself was scheduled to be executed by the State of Georgia. Davis had been tried for and convicted of the murder of police officer Mark MacPhail, but recanted testimony and new evidence pushed activists to argue there was too much doubt to warrant his execution, thus leading to the affiliated hashtag #TooMuchDoubt. Through the hashtags, a Change.org petition was shared encouraging tweeters to sign and demand Davis’s clemency. The petition, which garnered 258,505 signatures, was addressed to the State of Georgia’s Board of Pardons and Paroles and Chatham County district attorney Larry Chisolm.

It is impossible to overstate how penetrative #TroyDavis was on Twitter, from September 11 through September 21, the day Davis was unjustly executed. I cannot recall a single tweeter I followed who not only tweeted about #TroyDavis but also called on DA Chisolm and the Supreme Court of the United States as the justices deliberated over whether or not to stay his execution. There was even a vigil on Twitter: ten minutes without a single tweet at 7:00 p.m. on September 21, in the hopes it would sway the SCOTUS decision. Though our mission seemed to be failing at every turn, my entire Twitter feed remained engaged, making calls, encouraging action, saying virtual prayers. Briefly, it looked as though the SCOTUS decision would go our way, after Jeffrey Toobin reported that the deliberation was “unusually long.” Unfortunately, our efforts to save one man’s life were unsuccessful. When the DA failed to act, followed by the SCOTUS failing to act, the result was the state’s murder of Troy Davis at 11:08 p.m. In that moment, I could feel the devastation ripple across Twitter. We contemplated what it meant that all these people could act in unison and still not save one life, and what it meant to be at the mercy of the criminal justice system. Though the campaign to stop the execution of Troy Davis was unsuccessful in saving his life, it did succeed in giving this subgroup, which would soon become known as Black Twitter, a collective sense of obligation [emphasis added].

I share this long excerpt in its entirety because it captures the tone of the book. Here, hashtag activists successfully coordinated a symbolic action, a Twitter vigil, though how exactly they distinguish these actions from the aforementioned deficient performativity, or by what mechanism they expected not tweeting for ten minutes to affect a SCOTUS decision, remains unclear. It also raises a more fundamental question: Is this really activism?

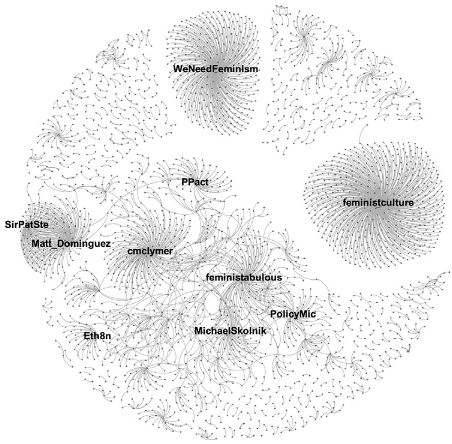

We don't get a definition of activism in general, so I offer my own: Power, by and large, comes from groups of people collaborating towards a common goal, be it the police, a union, the army, a company, a political party, etc. Activism is building power in opposition to entrenched and institutionalized power structures, usually by organizing coalitions of ordinary people. The organizational form that hashtag activism creates is a hashtag network, a group of people connected entirely within and by Twitter.

That means that, in addition to Twitter's constant mediation and strictly enforced brevity, hashtag activism comes with another dangerous side effect: Convincing people to tweet in support of a cause is, first and foremost, convincing them to tweet. Twitter uses users at least as much as users use Twitter, but the relationship is asymmetric: Elon Musk could decide tomorrow that all Twitter users are to receive a notification calling for violence against Communists and Jews, and there's nothing that hashtag activists could do about it. Even showing the efficacy of hashtag activism, as this book set out to do, relies on Twitter making the data available to researchers, which the authors note is no longer available. So, while calling Twitter-dunking or not-tweeting "activism" is dubious, building these networks is probably fair to call activism, but it's ineffective activism, a conclusion that the text itself supports.

When measuring the success of various hashtag-coordinated activities, the book usually relies on a combination of sincere anecdotes and data available from within Twitter, like counting shares, retweets, and/or listing the many, many celebrities who engaged with it. A few times, these celebrities are famous for their activism, but, much more frequently, they're, say, musicians or actors. Sometimes, a change.org petition might gather an impressive number of signatures, or the hashtags' virality itself makes it to the news. This last one is a real-world impact, even if it is a little meta, but it's hampered by the aforementioned concision and with problems of undemocratic messaging, which we'll discuss later.

Outside that, by my count, we get evidence of direct outside-Twitter impact exactly two times. The more compelling of the two was the case of CeCe McDonald, a black trans woman who killed one of her assailants with a pair of scissors while defending herself from their transphobic and racist attack, for which she was sentenced to 3.5 years in a men's prison. Twitter responded to this obvious injustice, and, though she remained locked up in a men's prison, she was given access to her hormone treatment, which she was initially denied. The second was when one of the jurors in the George Zimmerman trial tried to write a cash-grab of a book, which the publisher dropped after a public pressure campaign. In both cases, it's not clear to me how important hashtag activism itself was. The case for its role in the second example seems stronger, but, in the first example, the ACLU also got involved. The authors do explicitly say that hashtag activism is not a substitute for other kinds of work, but, outside these examples, most of the evidence for the efficacy of hashtag activism relies on counting engagement or moving anecdotes. Absent a compelling theory of change stemming from this engagement, evidence for efficacy is lacking.

If we combine the inconsistent analyses with the lack of evidence for the efficacy of hashtag activism, then we must ask: What exactly is their project here? Because even if they did conclusively prove that hashtag activism can work, they'd still be answering the wrong question, and it's here, at the core of my disagreement, that we find what it means that all these people could act in unison and accomplish nothing.

According to Pew, some 40% of Americans have a positive view of "socialism" (whatever that word may mean to them). A similar, if slightly smaller, number have a negative view of capitalism. Trump's favorability is only slightly higher than that of socialism, and has at times dipped below, yet the American fascist movement that he leads is powerful, while the American left is so tragically weak that almost all my friends have medical or student debt.

In other words, there are enough of us, but we are ineffective and powerless. It's not just about changing hearts and minds. How we choose to organize matters. According to this report, which may or may not be reliable, the average user spends over two hours on social media every single day, yet my local activist community, even in Vermont, in the supposedly-lefty-haven of Bernie Sanders, is always the same handful of people. Telling people that they can change the world by tweeting when we already tweet so much would be a dubious project even if it had been convincing.

To be clear, I am not arguing that people should stop using Twitter, or even that Twitter isn't a useful tool for activists,3 but I am arguing that networks of people using a hashtag are not viable organizational structures capable of challenging power in the robust and sustained manner necessary to actually win, though they can sometimes appear so. The authors do say explicitly that hashtag activism is not a substitute for other kinds, but their defense of the practice is so robust, and their connections drawn from hashtag activism to other kinds of activism or real world impact so few, that it's difficult to articulate what exact role they imagine it could play.

#HashtagActivism, however inadvertently, exists in an identifiable tradition. Existing forms of power will always try to convince us that the best or even the only political choices that we have involve working within and for them. The US Democratic party, for example, says that our only political choice is a vote, obviously for them.4 Unhappy with your options? Vote harder. This book argues for the merits of organizing under the purview of existing power. Their core project is to argue that "Twitter Made Us Better," the title of Jackon's op-ed in The New York Times promoting the book.

But the organizational dynamics of hashtag networks are pathological precisely because they are those of Twitter, a for-profit social media company. The networks in this book consistently end up with a de facto celebrity representative as the central node in a larger network. The authors constantly cite this as evidence for the hashtags' success and influence, since that means that it reached culturally influential people, but it also reveals a profoundly undemocratic structure with unelected spokespeople. Like brevity, deferring to people who are already important is structurally conservative, since the people at the top, by and large, benefit from the system as it exists today. Even the words of the hashtags themselves are the products of whatever tweet happened to go viral, the mechanics of which are almost completely opaque, not the considered messaging resulting from the activists' deliberation. Any organization of activists without control over what it says and who says it is, at best, dysfunctional, and probably easily co-opted.

More radical forms of organizing are both possible and necessary. We should control our organizations collectively, in their entirety, and, unlike using Twitter, it will not be convenient. In fact, I guarantee that it'll be a total pain in the ass, because democracy isn't easy. But when we build a democratic movement, we get to decide what it does. We need not limit ourselves to the options that other people give us, like tweeting or voting. We can strike. We can stop paying our medical bills, or our rent, or our loans. We can stop the police from evicting our neighbors. We can physically shut down fossil fuel infrastructure. We can ██████████, or ████████, or even ██████████████ the ██████████████ and ██████████, because, when we are organized, we can do literally anything that we have the numbers and will to do. That's what power is, and power is what good activism ought to build. That is what hashtag activism can never accomplish.

To give an example of excellent activism, Berlin is on the precipice of expropriating its 12 biggest landlords. Unlike tweeting, which can go viral overnight, activists started small, organizing tenants, doing tedious on-the-ground work. That hard work transformed a bunch of individual tenants being squeezed by for-profit companies into an organization that won a non-binding city-wide referendum with 60% of the vote to expropriate their landlords. Now, they're organizing a binding one. When they win, they'll expropriate 243,000 rental apartments. Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Berliners' material circumstances will change dramatically. If you hate your landlord, or your job, or your healthcare system, or the impending destruction of our ecological niche, tweet about it if you want, but then get organized, because the prospect of suddenly reaching a lot of people or even catching a celebrity's notice on Twitter will always be enticing, but any such success is fleeting. Good activism builds on itself.

The internet is full of political possibility. Through it, I, and now you, know about this campaign (unless you already knew of it, in which case, you too probably learned about it from the internet). Likewise, through that same magic, you can speak to the organizers involved, as I have, when they gave a talk hosted by INDEP, an organization that couldn't exist without the internet. The opportunities are real and powerful, both for us and for those that we hope to defeat. Exactly how to navigate this is a debate worth having, and it's here that I again agree with #HashtagActivism. Though I find myself on the opposite side, I'm grateful for scholarship that takes the issue as seriously as I do.

Because I had to cut so much of this post for length (it's still way too long), I want to reiterate McLuhan's influence, as well as that of the SPEAKING framework, found in footnote 2. This post also echoes many arguments from all over the leftist canon. In particular, while writing this, I often thought of Rosa Luxemberg's critiques of Bernstein in Reform or Revolution, as well as those of many of her contemporaries.

Thanks to Tom O'Brien for always reminding me that, at its core, politics is always and can only ever be about social relations. I could hear his voice in the back of my head continously whispering as much while I read #HashtagActivism. Go listen to his wonderful podcast, "From Alpha to Omega," or support the book that he and Donal Ó Coisdealbha are writing, The Classless Society in Motion. Also thanks to both Donal and Ferdia O’Driscoll for their feedback on some of the larger ideas here, like what activism means and how change happens, though the blame lies entirely with me.

1. We've also discussed this "democratizing" here and here.

2. For example, sociolinguists developed the SPEAKING framework specifically because understanding speech requires understanding its context. It includes the following components, upon which I'll be drawing throughout this post:

- Setting and Scene

- Participants

- Ends

- Act Sequence

- Key

- Instrumentalities

- Norms

- Genre

3. They should and it's not.

4. To paraphrase Chomsky, voting is something that we take 10 minutes to do every year or two, then we get back to work.