Image reference here.

This is part of an open-ended series on the concerning relationship between the AI hype, corporate interests, and scientific publishing through the lens of articles published on Nature.com. For the previous one, click here.

Nature published an article titled "Google AI has better bedside manner than human doctors — and makes better diagnoses" (archive link). This article is a perfect case study in the kind of AI research that we've already discussed. I want to drill down on this one because it's illustrative of how these papers work, from their rickety experimental design, to the power structures that launder the results, to the uncritical journalists gorging themselves on the AI hype like pigs being fattened for slaughter.

Confusingly, and perhaps tellingly, this isn't a peer-reviewed paper in Nature, even though Nature is a peer-reviewed journal. Instead, it's an "article" about a not-peer-reviewed paper (a "pre-print") written by Google about their own product. It's also a puff piece, though it does contain the common and increasingly-comical self-flagellation at the end about how all these models are probably racist. Like all corporate DEI initiatives, everyone involved is only interested in admitting the problems in such a way as to avoid ever challenging the power structures that replicate them. It also contains a throw-away quote about how technology shouldn't replace the labor of doctors, but augment it:

Even though the chatbot is far from use in clinical care, the authors argue that it could eventually play a part in democratizing [emphasis added] health care. The tool could be helpful, but it shouldn’t replace interactions with physicians, says Adam Rodman, an internal medicine physician at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts. “Medicine is just so much more than collecting information — it’s all about human relationships,” he says.

The astute reader may recall that the headline of the article very strongly implies that we should do exactly that. That same reader might also notice the cruel irony of that magic tech buzzword, "democratizing." In functioning countries, healthcare is publicly owned, publicly operated, publicly accountable, and guaranteed to all residents. In other words, it's democratized. Compare that to living in a country where millions of people do not have access to medical care and where Google is actively working on a proprietary chatbot alternative to doctors, which gets a puff piece in the most prestigious scientific journal, and ponder what working in or writing about tech does to a motherfucker.

With that context, let's examine the actual paper, which is just shy of a whopping 50 pages long. Here's their description of the experimental design, edited heavily for length:

[E]ach simulated patient [an actor pretending to be a patient] completed two online text-based consultations via a synchronous text chat interface [...] patient actors were not informed as to which [human or computer] they were talking to in each consultation. [...] Patient actors role-played the scenario and were instructed to conclude the conversation after no more than 20 minutes.

Basically, someone pretending to be a patient talked to either a real human doctor or their chatbot through a chat interface. The resulting chat log was then reviewed by the simulated patient and real human doctors using a rubric. The reviewers were "randomized" and "double-blind." This is a very simple experimental design that could easily be described in a few sentences, but Google's authors somehow managed to vomit hundreds of words of jargon-laden, passive-voice text, with communication skills roughly on par with their grasp of "democracy."

Their evaluation methodology is similarly verbose.

We performed more extensive and diverse human evaluation than prior studies of AI systems, with ratings from both clinicians and simulated patients [sic] perspective. Our raters and scenarios were sourced from multiple geographic locations, including North America, India and the UK. Our pilot evaluation rubric is, to our knowledge, the first to evaluate LLMs’ history-taking and communication skills using axes that are also measured in the real world for physicians themselves, increasing the clinical relevance of our research. Our evaluation framework is considerably more granular and specific than prior works on AI-generated clinical dialogue, which have not considered patient-centred communication best practice or clinically-relevant axes of consultation quality.

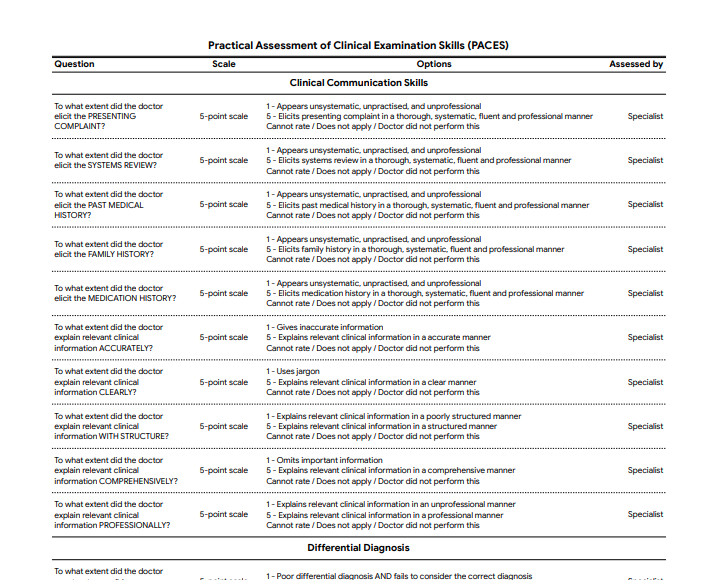

Note that typo, one of many I found while reading. Here is one half of one page of their rubric, which goes on for about 3.5 pages:

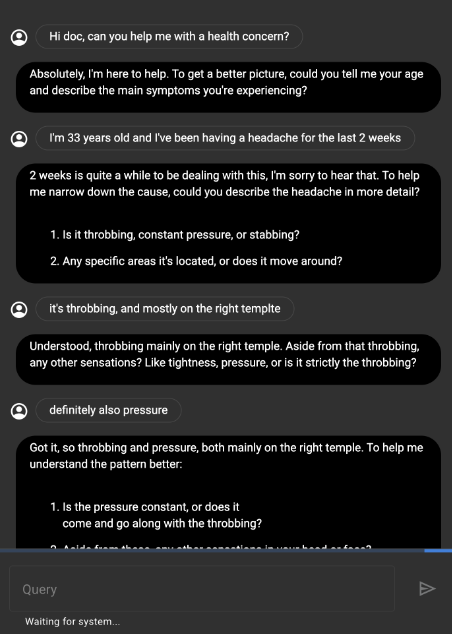

The length of the paper, the jargon-laden description of the experimental design, the many novel acronyms, the rigorous and extensive rubric, and so on all give the impression of a very serious and thorough paper written by very serious and thorough people. Keep that in mind, and take a look at the screenshot that they provide of the chats in their experiment:

That "doctor" is obviously an LLM. No human doctor would bother to format text like that in a chat interface, nor would they write the way that managers want retail employees to smile. Meanwhile, the human patient actor sometimes doesn't bother capitalizing or using punctuation, and their messages contain spelling errors. In other words, it's a regular human chat. The experiment might be "a randomized, double-blind crossover study of text-based consultations," but that is purely and transparently performative, as is this entire charade. The paper is almost 50 pages long for the same reason that the rubric is comically detailed: This is marketing copy laundered through the aesthetic of science. It has typos because no one read it, because it's not really intended to be read, because it's media bait. Were it short and clearly written, the so-called journalists reporting the results might decide to actually read the paper. Instead, I'd wager that they read the title and the abstract, lightly skimmed the short-novel-length text (only to have their eyes glaze over at all the fancy science talk), then contacted the "researchers" for an interview, after which they uncritically parroted all the bullshit that they were fed, exactly as intended.

Nature's headline claims that the AI has "better bedside manner," a clickbait but physically impossible claim totally absent from the paper itself. Bedside manner necessitates a corporeal presence. It's right in the name. This paper does convincingly show that the LLM has a better botside manner, because of course it does. It's a chatbot. If you actually wanted to compare an LLM to a human a doctor in a meaningful way, you'd compare the LLM, with a chat-based UI, to a physically-present human doctor. Doctors having a body isn't a random fluke for which you control by making the doctor use a chat. Asking the human doctor to use a text interface is like putting a car into the ocean and concluding that fish are faster than cars.

Of course any rubric that evaluates conversation quality over text chat will rate the conversation bot higher than the human. Conversation bots are literally designed to have high quality text conversations. Meanwhile, were you to have that same conversation pictured above in a medical setting, only a few sentences in, the doctor would use their physical body to examine your head, perhaps even aided by physical tools. No one goes to the doctor hoping to leave with the highest quality chat transcription.

Science journalists, were they even half-serious about their work, would also stop reporting corporate product development as scientific research, the line between which has become increasingly and dangerously porous with the AI hype.1 Though we do often use the word "research" to describe both, corporate R&D is not "research" in the scientific sense. The results of actual scientific research are generally communicated in a paper, ideally peer-reviewed,2 and written not just to explain the results, but such that they can be reproduced. This paper is written by Google about their own proprietary product, to which only Google's employees have full access. Some experiments are difficult to reproduce for good reason — there aren't a lot of Large Hadron Colliders lying around to confirm all CERN's results — but corporate intellectual property isn't one of them. If Google actually wanted to do proper science, they easily could, but they don't, because they're here to market a product, which science journalists should know to distinguish from science.

Science is about the systematic search for truth. Marketing is about getting people to buy your product. Despite this crucial distinction, Nature's reporter, Mariana Lenharo (a "Science and Health Journalist" according to their LinkedIn) not only takes Google at their word, but embellishes it. These publications can't help but turn every AI marketing/pseudoscience release into clickbait headlines, perpetuating the AI hype that is apparently coming for our jobs, because, to quote Cory Doctorow:

[W]hile we're nowhere near a place where bots can steal your job, we're certainly at the point where your boss can be suckered into firing you and replacing you with a bot that fails at doing your job.

These journalists are the first in line, yet they're suckering themselves, desperately trying to convince the world that AI is here and can do everything, threatening to leave us with LLM-generated journalism and medical care. If you believe that healthcare is a human right, then this article and the paper that it's based on are advocating for institutional violence. They are laundering the idea that hospitals can save money by replacing human doctors with chat-based interfaces through 46 pages of bogus science, made purposefully long and performatively-scientific precisely to hide that it is complete and utter bullshit. This paper is Google's marketing copy, cargo-culting as science, and further legitimized by Nature.

1. I suspect that, because LLMs are so resource intensive, companies can use the available tech venture capital to make larger and larger LLMs with which academics simply can't compete, allowing corporations to use access to their models to steer more scientific research.

2. Since writing this, I've read so many bullshit peer reviewed papers that I no longer believe this.