Illustration used this reference.

Anyone who played Roller Coaster Tycoon made the same discovery: You can create a path into a certain area of your park, and once guests wander in, you can delete the paths, then charge the now-trapped guests exorbitant prices for food or bathroom access, and they'll pay it. At the time, I thought that this was a funny glitch. I realize now that it is a glitch, but not of the game. Those with power can and do make arbitrary rules that extract arbitrary wealth in obviously unfair ways.

Many of the biggest tech companies, like those formerly known as "Facebook" and "Twitter," became so by doing exactly this. They created an open space, in which they were good to their users, and then, once everyone was there, walled it off. I discussed this in my very first post about Substack, which is, predictably, under ever-increasing scrutiny. This is a specific type of what Cory Doctorow calls Enshittification, in which internet companies become shitty in specific and predictable ways.

Though the internet is new, this kind of rent-seeking is perennial. English peasants in the sixteenth century had common rights to land, which they used collectively, for pasture, firewood, and so on. The nobility hated this, since they couldn't extract rents from that land, which allowed the peasants to subsist independently of the nobility, thereby depriving them not just of the peasants' rents, but their labor, so they passed laws enclosing it. This created an urban workforce of dispossessed peasants reliant on wage labor to live, a necessary component of capitalism.

I and others have argued that this situation is analogous to what's currently happening on the internet. Where once we could freely browse, we now increasingly find login walls, paywalls, or notifications telling us that, to access this content, we need to download the app, all so an ever-shrinking group of people can extract rents from cyberspace. Though the harms are more diffuse than the mass-eviction of peasants, they're no less real, or less dire. In our supposed-democracy, a few companies mediate, moderate, and collect rent on our public squares, the harms of which are becoming increasingly well-understood. In the global south, these companies are somehow even more irresponsible, with horrific results.

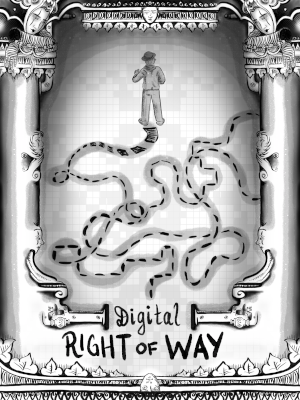

Resistance to enclosure, throughout history, has existed in many forms. There were rebellions, uprisings, and riots throughout the 15th and 16th centuries. They often ended quite tragically. Much more recently, in the 20th century, British activists organized for a right to roam, or for the public to have the right to walk through the countryside. They agitated, organizing mass trespasses, and they had legislative success, most notably, the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000, which granted the right to roam on some kinds of land, and, crucially, legally protected historically-used footpaths, creating the delightful network of public footpaths that crisscross the countryside. The law gave activists a grace period to find old paths and thoroughfares on old maps. Once identified, those public paths, which go through private land, received legal protection. The fight is far from over, and the harms of enclosure live on, but this is a meaningful mitigation from which we should learn.

I propose that if a company wants to grow by allowing open access to its services to the public, then that access should create a legal right of way. Any features that were open to users cannot then be closed off so long as the company remains operational. We need an Internet Rights of Way Act, which enforces digital footpaths. Companies shouldn't be allowed to create little paths into their sites, only to delete them, forcing guests to pay if they wish to maintain access to the networks that they built, the posts that they wrote, or whatever else it is that they were doing there.

Companies aren't going to like this idea. Many of you are probably already familiar with the tragic story of Aaron Swartz, in which prosecutors threw the book at one of the internet's best at the mere suggestion of open access, which ended in his death. Likewise, there's Alexandra Elbakyan, the creator and maintainer of Sci-Hub, and a genuine hero. Sci-Hub righteously violates copyright to provide free access to research papers to anyone in the world, bypassing the offensive rent-seeking practices of major publications. Everyone uses Sci-Hub, including me. She has probably single-handedly done more for science than anyone else alive, and for her service, she cannot go anywhere with an extradition treaty to the US.

This good work is deeply political. The clear and repressive government response definitively rebuts any attempt to see open access to information as somehow "apolitical." In our quest for an open internet, we need a comprehensive political program, complete with direct action, like Sci-Hub, and policy proposals. To that end, I propose that, as a part of this program, we demand an Internet Right of Way. We should lobby governments to stop companies from closing off access to cyberspace historically open to the public, and so long as things created by the public — publicly-funded research, tweets, essays, dank memes, etc. — remain closed off, it is right and good to expropriate those things by any means.