Notes: There will be no spoilers in this post. Mushroom cloud image background is from here.

"In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation."

— Guy Debord (The Society of the Spectacle)

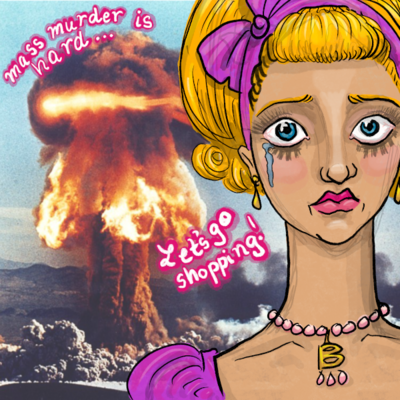

This summer, "Barbie" and "Oppenheimer," two well-funded and seemingly opposite movies, were released on the same date, creating the tragic portmanteau "Barbenheimer," which I am now forced to repeat. This is a strategy known as counterprogramming, which, according to Wikipedia, is a "marketing strategy to distribute a film that appeals to audience demographics not targeted by another film." Since "Barbie" is explicitly for women, we must conclude that serious movies about war, science, and genius are for men.

Before we go on, I am going to continue to be very mean about these movies for the rest of this post, but I want to make one thing clear: Just because our cultural production is almost entirely corporate nihilism does not mean we can't enjoy and embrace the void. If you liked either or both of these movies, that isn't bad or wrong or shameful. I too enjoy much of our empty and meaningless culture.1 It's really all we have. I'm not here to judge you; I'm here to judge us all, collectively.

"Barbie" is yet another high-budget movie made with existing intellectual property. These are fracking operations; they use modern techniques to extract new value from preexisting intellectual property previously considered depleted, turning our culture into a toxic slush we are all forced to drink. This time, the IP being revived is the doll famous for, among many other things, telling girls things like "math class is tough," "want to go shopping?," "okay, meet me at the mall," and "will we ever have enough clothes?" Somehow, this sexist corporate brand has been transmogrified into such a woke feminist masterpiece that Ben Shapiro himself has spent hours complaining about it.

My producers dragged me to see ‘Barbie’ and it was one of the most woke movies I have ever seen. My full review of this flaming garbage heap of a film will be out on my YouTube channel tomorrow at 10am ET.

Since I have not seen the movie, everything I know about it will be based on a totally sane and normal New York Times opinion piece (but I repeat myself), titled I Saw ‘Barbie’ With Susan Faludi, and She Has a Theory About It. The piece starts with a real banger of a paragraph:

Susan Faludi suggested we show up to the “Barbie” movie in a pink Corvette, but unfortunately, the only car available was a pickup truck. So that was how one of the world’s leading feminists and I showed up to her local mall: in a 2002 black Toyota Tacoma, with tickets to Auditorium 2 for “Barbie.”

This is a hilarious and masterfully-set scene, in which two women, one a feminist author, go see a movie for girls in a car for boys. The piece continues:

There are few toys quite so confounding as Barbie. Even her origin story: She was based on a sex doll for men, but somehow marketed to mothers for their daughters. Barbie has been a protest slogan (“I am not your Barbie”), a bimbo (remember “Math class is tough” Barbie?), an eating disorder accelerant. In one particularly clever protest against the doll, she had her voice box swapped with G.I. Joe’s, so suddenly she said, “Vengeance is mine!” and he said, “The beach is the place for summer.” But Barbie has also been a lawyer, a pilot, an astronaut and the president. She has never married, lives alone and does not have children.

First, a quick correction: In "I am not your Barbie," Barbie is not the protest slogan. It is the complete opposite. The slogan protests what Barbie represents. Being the object of protest, a "bimbo," and an "eating disorder accelerant" are actually all the same thing.

More fundamentally, there is actually nothing mysterious about Barbie. It is as straightforward a cultural product as there could possibly be. The brand is what it needs to be to make money. First and foremost, Barbie has always been, and continues to be, sexy. It's easy to imagine Barbie as a lawyer, an astronaut, and so on, but it's much harder to imagine a Barbie that isn't beautiful. She began as a literal sex doll, and is today portrayed by Margot Robbie. Beyond the obvious and continued sex appeal, it's a weathervane. When explicit sexism is profitable, the dolls are the transubstantiated patriarchy through which we pass down the objectification of women from one generation to the next. When sexist symbols are not profitable, Mattel, Inc., the owners of the Barbie brand, are able to deploy bottomless capital to convert Barbie into a girlboss, confounding the cultural critics and luminaries at the NYT. The author of this piece herself walks right up to this point in the very next paragraph.

The movie seemed as full of contradictions as the doll [Editor's note: 🙄]. It was promoted through a marketing campaign that had more licensing deals than Barbie has outfits: There were Barbie clothes and Barbie makeup and ice cream and vacation packages and a takeover of the Google home page, which is currently filling my screen with pink explosions every time I try to fact-check this essay. But it also had a director — Greta Gerwig — with indie street cred, and early reviews focused on the film’s subversiveness. Ms. Gerwig, it seemed, had managed to make Barbie satisfyingly self-aware, likable and mockable; she called out the hypocrisy of the manufacturer — Mattel — while getting its blessing on the project. And then, somehow, she — and the company — marketed it all back to us.

From there, the piece continues in the way of the best op-eds — an uninteresting person explains a subject through the meta-story of their own experience with it, lacking any insight or entertainment value. If I may indulge in some of the same, I stopped reading a few paragraphs later, unable to recover from this:

Indeed, Barbie begins with a homage to Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey,” with little girls playing with baby dolls — which, as the narrator explains, were the only dolls available to girls back then. So when Barbie — an adult doll — comes along, it’s an epiphany: There’s more to life than motherhood! The girls smash the baby dolls.

I then turned to the murder of somewhere between 129,000 and 226,000 souls as a palate cleanser. "Oppenheimer" tells the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the "father of the atomic bomb," head of the Los Alamos Laboratory, and man who was apparently almost single-handedly responsible for the single most horrific and devastating technology the world has ever known, because of which we all live an hour away from nuclear apocalypse for the rest of time. The apparently not-satirical website Highbrow Magazine wrote a review of the movie, titled 'Oppenheimer’ Demonstrates the Cost of Genius and Ambition, which more-or-less captures what I have absorbed from popular culture. The review starts with an extremely questionable atomic bomb pun ("While the film isn’t as bombastic as the marketing would make one believe"), and then goes on:

Murphy’s Oppenheimer is the portrait of a flawed man whose curiosity and ambition lead him to scientific breakthroughs that were revolutionary, horrifying, and inevitable. He is a man haunted by his mistakes and hubris before almost being destroyed for his conviction. What makes it all work is the theme of technological discoveries that also threaten to destroy us, an idea that is extremely relevant to today’s world.

These technological discoveries are central to the story we tell about World War 2. It was often (and sometimes still is) called "the physicists' war." One of my all-time favorite scholars, Prof. David Kaiser, has written extensively about this phenomenon. I will be drawing heavily from his work for the next few paragraphs.

Kaiser explains that the first world war, famous for its chemical weapons, had been dubbed "the chemists' war." With the advent of new technologies like radar and the atomic bomb, the explanation for calling the unfortunate sequel "the physicists' war" seems obvious, but usage of the term predates either of those technologies. Here's Kaiser again:

Modern warfare, it seemed, required rudimentary knowledge of optics and acoustics, radio and circuits. [...] The army, for example, wanted the new courses to emphasize how to measure lengths, angles, air temperature, barometric pressure, relative humidity, electric current and voltage. Lessons in geometrical optics would emphasize applications to battlefield scopes; lessons in acoustics would drop examples from music in favour of depth sounding and sound ranging.

So acute was the need to teach elementary physics that a special committee recommended that university departments discontinue courses in atomic and nuclear physics for the duration of the war so as to devote more teaching resources to truly essential material [emphasis added].

As we all know, the so-called physicists' war ended with the horrific bombings at Nagasaki and Hiroshima. The government's atomic bomb program was obviously highly secretive, but, in preparation for dropping the bomb, the government had physicist Henry DeWolf Smyth write a report to be released to the public.

Security considerations dominated what Smyth could include. Only information that was already widely known to working scientists and engineers, or which had “no real bearing on the production of atomic bombs”, was deemed fit for release. Little of the messy combination of chemistry, metallurgy, engineering or industrial-scale manufacturing met these criteria; these aspects of the huge project, crucial to the actual design and production of nuclear weapons, remained closely guarded.

So Smyth focused on ideas from physics, pushing theoretical physics, in particular, to the forefront. Ironically, most people read in Smyth's report the lesson that physicists had built the bomb (and, by implication, had won the war)

It is precisely because the theoretical physics was either already widely known or had no real bearing on the production of atomic bombs that, eighty years later, we have a movie about how a theoretical physicist was instrumental in the making of the atomic bomb.

This prestigious misunderstanding was released on the same date as "Barbie," which transformed the eponymous character from obviously sexist pieces of polyethylene plastic into an on-screen feminist hero, still palatable to corporate interests, yet still somehow upsetting the reactionary right, who much preferred Barbie before the transformation, leaving those of us who find the transformation offensive for the exact opposite reason bewildered.

These multi-layered episodes of bewilderment are both a commonly accepted fact of our online world and deeply, profoundly disorienting. Suddenly, we find ourselves defending Barbie's feminism from Ben Shapiro, which is somehow linked to the atomic bomb, only to learn that that strange link we previously thought was historical is itself based on a popular misconception and government secrecy. Our reality is malleable. With enough money and/or power, you can manifest a new one. Mattel Inc. had a sexist brand on its hands. They didn't want it to be sexist anymore, and now it's not. It's straight out of The Secret, except it shows the actual power of money, not the pretend power of thoughts.2

Is it any wonder that our society seems increasingly untethered from reality? In a way, the only thing that distinguishes a crazy internet theory from an accepted shift in reality is power. There was a time when, had a normal person tried to claim that Barbie is a feminist icon, we would have laughed at them. Pour a lot of money into doing so, and suddenly Ben Shapiro is calling Barbie the wokest lib to ever woke. Likewise, it easy to imagine an alternate reality in which the history of the bomb is well known, but a small group of online cranks blame all of it on a single Jewish theoretical physicist named Oppenheimer. Put another way, consider an existing conspiracy theory — Jewish space lasers. The physics of lasers have been well understood for decades, yet we don't have any space laser superweapons for any ethnoreligious groups. Were we to try to build one, it would be a monumental engineering effort, despite the well-known physics. When cranks try to claim that such a thing exists, smug fact-checkers explain that superweapons are giant engineering efforts, for which basic science plays an important but ultimately small role.

Knowing that, consider this New York Times review of "Oppenheimer." It calls Oppenheimer the "father of the bomb" more than once; it calls the movie "a great achievement in formal and conceptual terms, and fully absorbing, but Nolan’s filmmaking is, crucially, in service to the history that it relates." Throughout the entire review, it's clear that the reviewer is operating under the misapprehension that "physicists built the bomb." The "history it relates" is not real, but exists because it was more convenient for the government's desire for secrecy; it is a reality manifested by power. This same publication rightly criticized Marjorie Taylor Greene more than once for theories that, if you squint only a little, are uncomfortably similar.

How are we supposed to make sense of the world if it doesn't make any sense? Or, worse yet, what if the sense we thought it made is subject to change? It seems the truth is just whichever story has the biggest budget, but the internet has made attention and money indistinguishable. Gaining an audience and gaining power are increasingly converging. A new generation of manifestation influencers are peddling the same new age thought-magic as "The Secret," but if reality can be transmuted by power, and gaining an audience and gaining power are the same thing, then these manifestation influencers, by attaining influencer status, almost become self-fulfilling.

In an effort to defend ourselves from these ever-morphing realities, we become skeptics. We "question everything," a favorite slogan among online conspiracy theorists, but there are so many things. We are incapable of questioning every single thing that we've ever been told. When we try, we create a cosmological void within our souls with which humans cannot live, leaving us vulnerable and searching for something to fill it.

1. I am wearing a Star Wars t-shirt right now, as I type this. It is a fake tourism advertisement for Tatooine. I unironically love this shirt and exclaimed with glee when I found it at the thrift store.

2. This might help explain Oprah's enthusiasm for the book. For the ultra-wealthy totally accustomed to their money, their thoughts are powerful.

Acknowledgement: Thank you to the QAnon Anonymous podcast, especially their British correspondant Annie Kelly, for their invaluable coverage of and insight into the online and offline worlds of conspiricism.